The SV is the ultimate production version of the car that changed everything more than half a century ago. We’ll never see the likes of it again.

A distant mechanical rumble, a classically elegant viaduct stretching across a deep, grass-covered mountain gorge. The panoramic scene on the screen widens and lowers as a dark orange sports car enters, tiny in the frame, thundering across the bridge, exiting stage left.

Immediately the camera cuts to the cockpit as the car’s driver takes a tight left hand corner, blipping its throttle as a quartet of triple downdraught Weber carburettors opens up and the quad exhausts emit a shrill, intoxicating blare, channeling the music made by a dozen pistons. A couple of seconds later we see the car from outside, the camera panning as it continues its journey and that’s all it takes. Just 27 seconds into the opening credits of 1969’s The Italian Job and anyone with an appreciation for physical beauty is struck dumb by the side profile and the sonic theatrics of a Lamborghini Miura.

By the time Matt Munro’s crooning begins, his vocals washing over you like warm honey, for many viewers the film is already over; they’ve seen and heard all they need. Just half a minute of glorious carporn that turned the original supercar into a bona fide superstar.

Our personalities, our characteristics, our quirks, foibles and kinks are all the result of neural pathways etched into our brains during precious formative years. And for me as an impressionable youngster, the sights and sounds of that Lamborghini set me on a path from which I have never deviated. My love for automobiles was born the first time I saw that film’s opening scenes and the adoration I had for the Miura as an eight-year old boy has never diminished.

Like an itch I’d never been able to reach around and scratch, my desire to drive a Miura – any Miura – had remained unfulfilled. It was likely to remain a hero I’d never get to meet and, despite my attempts to reassure myself that it was possibly for the best, that pining never really went away.

Forget, for a moment, the nape-prickling bark from its engine when blipping the throttle between downshifts. Forget the forward-thinking, cutting-edge chassis construction dreamed up by a small team of excitable young men burning the midnight oil in the mid 1960s. Forget the legacy of this, the first genuine supercar. For me, the Miura is first and foremost a sculpture. It’s a piece of rolling art, the embodiment of physical perfection. It is without peer – no automobile, before it or since, has come close to this Lamborghini’s breathtaking beauty and raw sex appeal. If I could, I would have one in my living room instead of a television or even furniture.

I have never made any secret about my shallow appreciation for physical beauty – I’ve made some fairly disastrous decisions over the years because of being swayed by my eyes, while my brain screams at me to get a grip on reality. And my begrudging acceptance of never getting to experience a Miura from its driver’s seat has for years been aided and abetted by a half-hearted belief that it would be a disappointment anyway – like a date with a goddess whose voice and mannerisms just grate on the nerves, to the extent where you have to make a run for it. But when an invitation arrived at my office to join a handful of other journalists from around the world for a drive of the object of all that lust, there was no way I was going to turn it down.

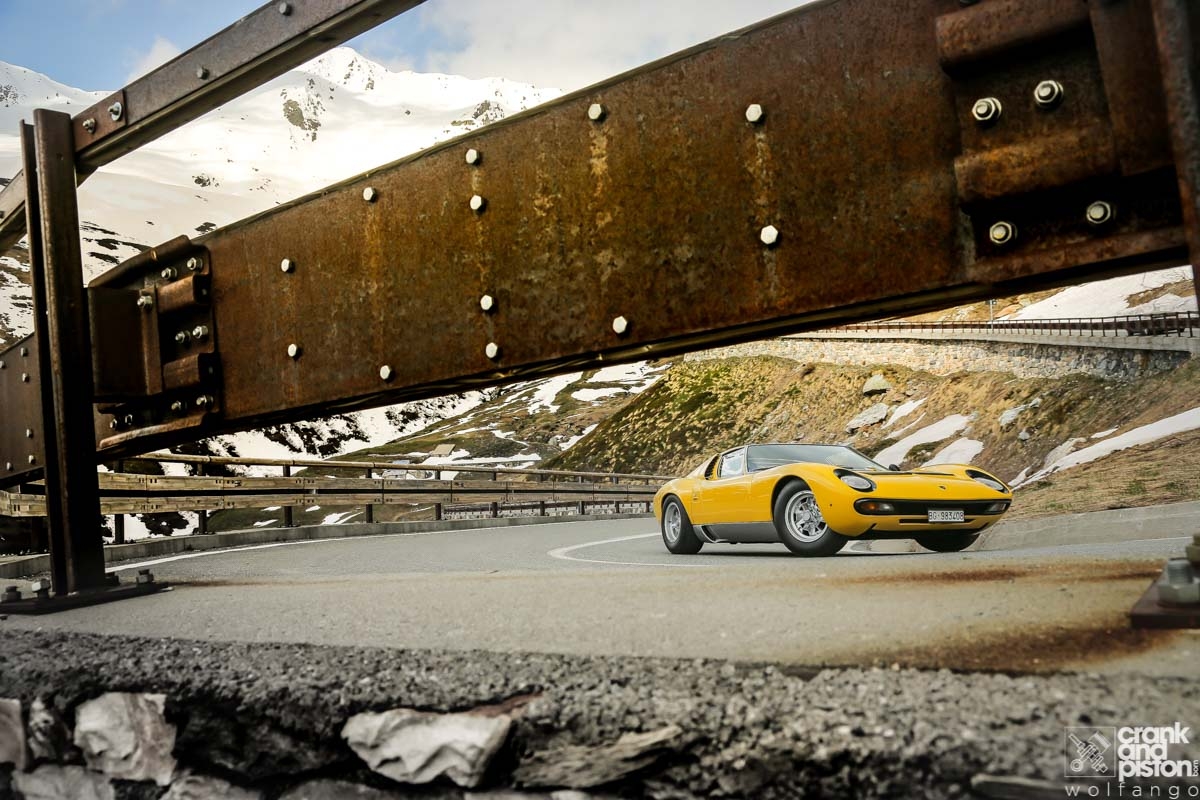

A drive of the Miura was tantalising enough. But there was much, much more. The route was to be the same road used at the beginning of that film and the car I was being offered to drive was none other than the mighty SV, the absolute apex of Miuradom. The SV (an acronym for Super Veloce, or ‘really bloody fast’) is one of only 150 ever built and is what the model should have been from the very beginning – wider, more aggressive, better resolved both visually and mechanically. The thought of having it to myself for an afternoon was almost too much to bear.

If you’ve seen the film (avoid the hateful Hollywood remake), you’ll know what I mean when I say the road is staggering, carving its way through the majestic Italian Alps where every view is one of absolute widescreen splendour. For three weeks I punched the air whenever I reminded myself of what was to come but there was still more to this event: I was going to be spending time with some of the people who brought the Miura to fruition in the 60s: design chief Gian Paulo Dallara and the man responsible for many of history’s most beautiful and outrageous car designs, Marcello Gandini – both legends, not just in Italy but all over the world. As one-off, never-to-be-repeated experiences go, this was a biggie.

The Miura’s reputation as the original supercar is entirely valid. Unveiled just three years after Lamborghini started building cars, it tore up the rulebook with a liberal application of engineering and design genius, the likes of which had never before been seen in a road car. Lest we forget, Ferrari’s answer to the Miura came two full years later in the form of the 365GTB/4, otherwise known as the Daytona – a traditional, front-engined GT.

Ferrari didn’t embrace the mid-engine layout for its V12 until 1973’s Berlinetta Boxer, old man Enzo having eschewed the idea, believing his customers would find having their engines amidships too much to handle. By the time the Boxer came along, the Miura was dead and the Countach was garnering Lamborghini even more worldwide headlines. Enzo must have been incandescent with rage, his thunder being stolen in such style by his upstart neighbor. Indeed, it still provides much amusement for the three ‘fathers’ of the Miura, who have graciously come along to help celebrate the life of this undisputed icon, Dallara, in particular, becoming animated when asked about the rivalry between the two companies.

Normally at this time of year, this section of the E27 highway (part of what’s known as the Great St. Bernard Pass) is closed, only opening once the last of the winter’s snow has finally melted away. But this is Italy and the authorities don’t usually take much convincing when it comes to anything to do with their country’s supercars, hence the road is still closed except for our scarily valuable convoy.

Before my time in its seat arrives, though, there’s the small matter of a hearty lunch in an Alpine log cabin restaurant. Sat at the table with me, the men responsible for the design and engineering of this trailblazing machine. Gandini, who is generally accepted as being the maestro who penned this beautiful shape on behalf of the Bertone design house, remains elegant, softly spoken and almost embarrassingly humble. He can’t speak in fluent English but through our translator he tells me that he really doesn’t know what the fuss is about. To him, this was simply one project and, once it was done, he moved on to the next one. This was just a job.

He smiles as he recounts the development team’s ‘meetings’. “It was just a small group of friends meeting up in a coffee bar every now and then, to go through what each of us was planning and thinking. I was the only designer and I did what I could do to work around engineering matters, which was helped by me being interested in mechanical things. And I was able to steer things in a way that meant the shape remained more or less unchanged from my original design. There was no committee, no big studios like there are today, it was a totally different way of working and we were able to act very quickly. Now you couldn’t design and engineer a car like the Miura in a few months – it would take years.”

Surprisingly, Gandini says he wasn’t influenced by the curves of the female form, something most onlookers assume, especially as he added black ‘eyelashes’ to the headlamp surrounds on the original design. “If anything,” he counters, “I took inspiration from the cars that had been coming out of America during the 50s and early 60s, particularly competition cars. There was a design language at the time that I just interpreted – nothing is over the top, there is just harmony inside and out of the car and I think that is why so many people say it is the most beautiful car of all time. The chassis, its dimensions and the beauty of its engineering needed a special body to clothe it – it was groundbreaking everywhere you looked.

“The Miura represented the end of an era in car design – after that shapes became much more angular, sharper and more aggressive. For me designing cars in that time was just a job like any other – a client had a requirement and I helped meet that. Some designs stand the test of time better than others but for me it’s the engineering that’s really important, which is why the Miura is so special. What these other guys did was simply incredible.”

It was, too, and Dallara in particular is extremely animated as he recounts the almost skunkworks way in which they contributed to this project – one that Ferruccio Lamborghini just let them get on with in their spare time as he thought they were all a bit mad. Taking inspiration from racing cars (the old man had no interest in motorsport), the engine and gearbox were mounted behind the cabin, transversely in a single unit with a shared sump, just like the original Mini (although separate oil reservoirs were incorporated for the uprated SV).

That engine, which had already made a name for itself in the 350GT and 400GT, is a masterpiece and, according to famed motoring historian, the late LJK Setright, is Japanese in origin. He swore blind it was Honda that designed it and there’s plenty of anecdotal evidence to back up his theories. In the way it goes and sounds, however, it could only ever be Italian.

To remove weight, the chassis had large circular holes cut into it. This removed substantial amounts of steel but did nothing to harm its rigidity, being the application of aircraft ingenuity in a road car. These young men in their early 20s, and they were ignoring convention at every turn, although Dallara remarks that none of them had the first clue that what they were doing would end up being so influential.

As for the Miura’s incredible physical form, Gandini says the only thing he’d have done differently “would have been a wider rear track, which is what came in with the SV anyway [in 1971]. We just couldn’t make it work in the short timeframe we had to come up with the original design, and the motor show car [Geneva in 1966] was only finished a few days before it was unveiled. The SV’s wider rear gives it better stance and allowed for wider rear lamps, as well as wheels and tyres that fill the arches properly – it’s what it should have looked like in the beginning.”

He’s absolutely right and, after our fireside conversation, I finally get the nod that my chariot awaits. As I walk towards the yellow projectile, I feel nervous and strangely apprehensive. I really, really don’t want to be disappointed, my life has been leading up to this point and there’s a very real danger that nothing could ever hope to live up to the hype I have laid upon its Marilyn Monroe curves.

I pull open the driver’s door by its dainty chromed handle, which neatly nestles within the side air intakes. The cabin is light and airy, despite the somber black hide trim – it’s a driver-focused environment with a panic grab handle for terrified passengers. I adjust my seat and adopt the only possible position: arms outstretched, legs splayed and feet all over the place in the search for three pedals.

With a twist of the key, the fuel pumps loudly whirr and that magnificent V12 snaps into life with an abrupt bark, threatening to stop altogether once the flare of revs subsides, necessitating the occasional blip of the throttle to keep it going until I select first. Any excuse.

The gearstick is spring-loaded and sits within an evocative open gate, which rarely helps in the business of driving really quickly. An extremely heavy clutch doesn’t help, either, but my initial takeoff is smooth and fuss-free while that lever takes some work to get into my chosen ratio – none of which bothers me in the slightest as it’s all perfectly familiar to anyone who runs a classic car. It’s all part of the appeal.

Almost any road car designed in the 1960s is bound to feel rather sedate nowadays but the Miura gives it all, with the engine only coming on cam after 4,500rpm. There is no red line on the rev counter and I feel compelled to stretch each gear as far as possible before reaching for the next one, all the while the Miura surging forward with relentless energy, accompanied by an omnipresent, delicious thrashing noise that rises from a guttural roar as I keep the throttle nailed through each gear, only changing when I reach 8,000rpm. Make no mistake, this is still a very fast car on the right roads.

The non-assisted steering is delightful once the car is up to speed, offering communication aplenty and only becoming hard work when carrying out three-point turns. The brakes, though, are where the Miura’s age really becomes apparent, especially when descending through tight hairpins. They feel like blocks of wood are doing the job of the pads and require an almighty shove to wipe off speed. So I do the only decent thing and use that seemingly unburstable engine’s resistance to help as I go down through the ’box.

There’s a feeling of lightness over the front end when attacking the corners that takes some getting used to, and I’m reminded of the reputation the Miura had in the early days, for getting almost airborne at its top speed. It doesn’t feel that dramatic but the weight feels distinctly rear-biased (officially, however, it’s 44/46) and an injudicious stab at the throttle easily sends the back end swinging waywardly – not recommended in someone else’s $1.5million classic but it’s relatively simple to regain control and, on this day at least, I know for a fact there won’t be any oncoming traffic.

Long before I’m ready to give up my seat, I’m waved in. My time is up and the Miura needs fuel and a rest – it’s been given a proper workout and, in the afternoon I’ve spent in its cabin, I have become so smitten by its charms that I almost physically ache when handing over its key, before watching forlornly as

this Lamborghini is put onto its trailer and ferried back to its museum home.

I will never forget these sights and sounds. The epic views that unfolded at every turn, the way the front wings curve gently away from the windscreen’s edge, the view from the mirror through the black slats that cover the engine, the large circular main dials and that small, chunky steering wheel, the relentless surge – they all were exactly as I had dreamed they would be. It’s better than I could ever have hoped.

That the Miura’s beauty is more than skin deep is its ultimate triumph, though. Everything about its design shows a fearless approach to engineering, where legislators and accountants were left entirely out of the picture. Those days will never return and, 48 years from now, when it turns 100, it will still be revered as the ultimate game changer.

| Lamborghini | Miura SV |

|---|---|

| Engine: | Mid-mounted V12, 3939cc |

| Power: | 385hp @ 7850rpm |

| Torque: | 294lb ft @ 5750rpm |

| Transmission: | 5-speed manual, rear-wheel drive |

| Suspension: | Independent, coil springs, anti-roll bar (front and rear) |

| Brakes: | Girling 267mm (front and rear) |

| Wheels: | 15-inch, magnesium alloy |

| Tyres: | 215/70VR15 (front), 255/60VR15 (rear) |

| Weight (kerb) | 1245kg |

| 0-100kph: | 6.7 secs |

| Top speed: | 300kph |

| Price when new: | $21,000 |

| Price now: | $1.5million |