When Ferrari launched the 360 Modena in 1999, the junior supercar was suddenly not so junior any more. At the 2003 Geneva show, the firm followed up with something even more special: a road car that effectively channelled the genes of the 360 Challenge one-make race car (with nods also to the 360 N-GT and 360 GTC FIA GT Championship racers). It was called the 360 Challenge Stradale and, bar the very-limited-run 348 GT Competizione, was nothing less than the first Ferrari road-racer since the F40.

There was something else motivating Ferrari, too: while the firm didn’t intend its wealthy clientele to buy a 360 CS then strip it down and prep it for Le Mans, it did envisage the CS making it onto the trackday scene – one that was becoming ever more prevalent at the time and one that Ferrari needed to cater for.

Not that the Ferrari screams about its intentions: there is no towering rear wing raised high in the slipstream; no ‘canards’ festooning the nose. The CS’s enhancements are subtle but no less effective. Post Stradale, the standard 360 looks a bit undefined, lofty, timid. The CS’s lower front air dam, deeper sides and subtly raised rear deck contributed to a 50 per cent increase in downforce, meaning 40kg more of the invisible force at 200kph. Useful, but comically smallfry when you consider the Performante has 750 per cent more downforce than the standard Huracán…

Given that the power increase would be minimal over the standard car, Ferrari knew weight loss was going to be the most effective way to increase performance. In the ideal lightweight specification, that reduction is 110kg – ‘ideal’ including the lightweight bucket seats, Lexan side windows with pull-back openers, and no radio. There are too many details to list here, but the fact that the interior is bare aluminium underfoot, the floorpan is carbonfibre (50 per cent lighter) and the wheel bolts are titanium gives you some idea. A kerb weight of just 1280kg means the CS sits exactly halfway between the regular 360 and the Challenge race car (1170kg with fluids) in terms of mass.

The Stradale also has the final incarnation of Ferrari’s original Dino- series V8, first seen in the 308 GT4 of 1974 and used in everything from Mondials to the F40. Blueprinted for use in the CS, with a slight rise in the compression ratio, reduced internal friction, polished intake ports and new intake and exhaust systems, it makes 420bhp (up 26bhp on the regular car, although some would say more given the Modena’s optimistic quoted power) at 8500rpm.

If there was something reassuringly traditional about the CS’s engine tuning, the transmission was decidedly modern. Ferrari, originator of the single-clutch automated manual during the 1989 F1 season, was quick to adopt two pedals in its road cars, and there’d be no manual alternative for the CS, though it does seem quaint today that Ferrari boasted of changes in Race mode ‘as quick as 150ms’, along with a separate Launch mode.

There’s more to impart about the Challenge Stradale, a lot more, but now is the time for driving – I simply cannot resist it any longer. And let’s get the obvious out of the way first: if there’s one thing that makes the CS feel old, perhaps even older than its 14 years, it’s that gearbox. None of us who drove it in its heyday could have imagined that there would be ’boxes like the Performante’s just over a decade into the future.

The nicest thing you can say about the Stradale’s Magneti Marelli single- clutch affair is that its crudity requires a level of interaction the driver of the new car simply wouldn’t comprehend; the cruellest is that, as with the BMW E46 M3 CSL, it’s a flaw that today comes close to ruining a near-perfect car, and that the desire to experience it with a manual ’box is almost overwhelmingly strong.

No matter. Wedged into the Stradale’s bucket seat, you feel the whole car tremor at idle with the energy of the V8. Pulling away I learn there are expansion joints on the Bedford track that I never knew existed: the CS tells you absolutely everything, and I mean everything, about the surface beneath you. Editor Gallagher puts it best: ‘Assisted by its cab-forward driving position, it’s as though you have the palms of each hand resting on the top of each tyre.’ There’s a lightness of touch, too – in the steering, the way the car rides bumps, changes direction. It’s a nimbleness that helps it shrink around you, makes it less intimidating. And when the tail begins to slide, it does so progressively, communicating clearly.

Select Race – the CS’s simplicity is very appealing, in contrast to the Huracán – and the gearshifts are quicker, while the surprisingly pliant ride firms up. It’s almost too much out on the road but, flying along between the hedges, you are totally immersed in the Stradale experience, the unfiltered sensations of air rushing over the car, debris being flicked up and, most of all, that engine getting to work.

It’s not terribly fast if you keep the revs low, but around 4500rpm it wakes up, both in terms of acoustics and energy. Jump on the throttle now and the intake flaps crack open so aggressively the sound is like a pair of Samurai swords being scraped together. And what engine noise: a brutal, tearing howl as the CS leaps forward. Hit the left-hand pedal and it’s replaced by the roughness of the superbly effective carbon-ceramic brakes, donated by the Enzo and like two sheets of industrially abrasive sandpaper being rubbed together. Gearbox and all, it’s one of the most exciting, absorbing, desirable cars I think I’ve ever driven.

The Stradale was followed by the even more outrageous 430 Scuderia, which upped the ante for power (503bhp), aero and, most notably, the electronics for the gearbox and the chassis. Then there was the 458 Speciale, the ultimate incarnation of the high-revving, naturally aspirated lightweight Ferrari road-racer.

It took a while before Lamborghini decided to play Ferrari at its own game. The Gallardo was an altogether different proposition when its meaty V10 and all- wheel drive appeared towards the end of the 360 Modena’s production life. It wasn’t until 2007 that Lambo unleashed its own ‘CS’ in the form of the raw, raucous Superleggera (up just 9bhp on the regular Gallardo but 100kg lighter), following it up with a Mk2 version in 2010, the Spyder Performante and even more aggressive Super Trofeo Stradale a year later, and finally the Squadra Corse of 2013. And now we have this matt orange and ‘THE PERFORMANTE OFFERS A COMPLETELY DIFFERENT DRIVING EXPERIENCE, BUT ONE THAT’S EVERY BIT AS INVIGORATING’ bleached bronze animal parked before us: the Huracán Performante.

Initially, the Performante seems true to type. It is lighter than the base car, albeit by only 40kg this time, thanks to extensive use of carbonfibre – in this case the ‘forged’ variety, using chopped fibres in a resin, which looks curiously like black mahogany. Inside and out, it feels consciously styled, unlike the purely functional CS, from the flip-up starter button ‘protector’ to the extravagance of its exterior forms. It works hard for your attention, and inevitably gets it.

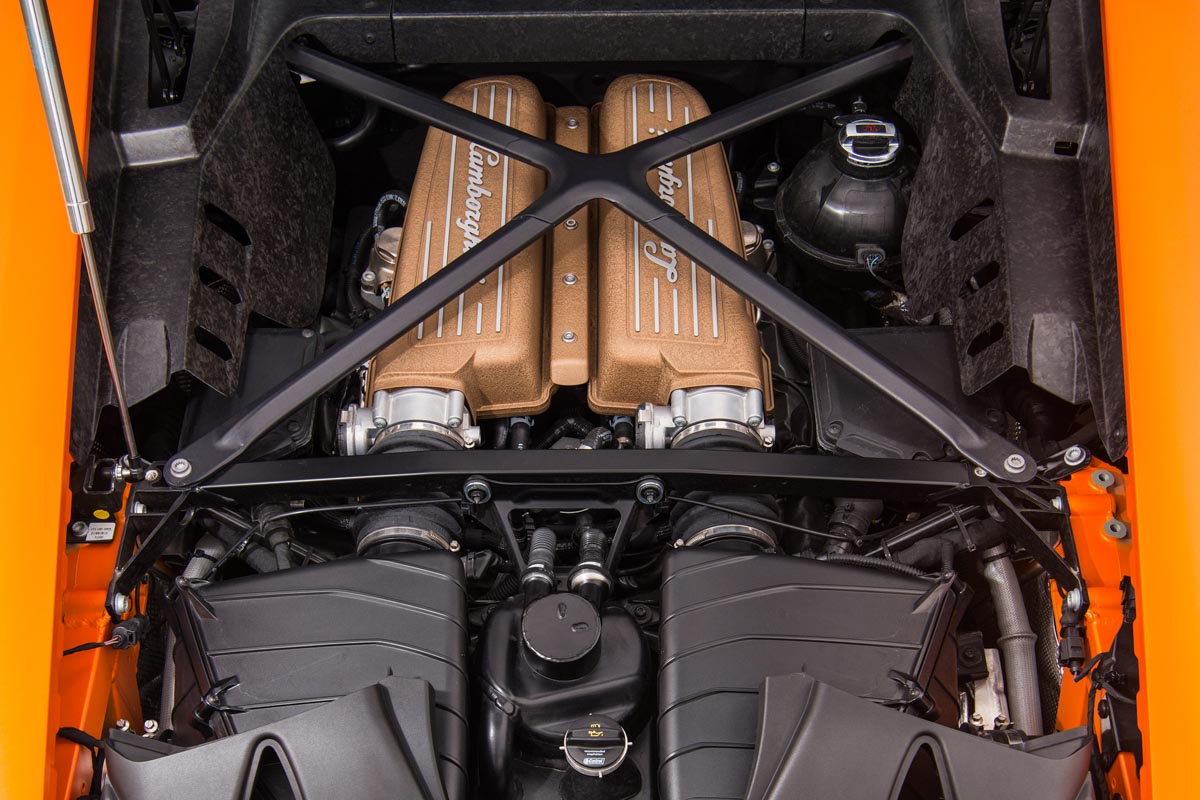

On road or track, the Performante offers a completely different driving experience to the Stradale, but one that’s every bit as invigorating. As with the CS, and despite all the other tech on show, the Lambo is defined by its engine, although again their characters are very different. The gains on paper over the standard V10 are small, an additional 29bhp meaning a peak of 631bhp at 8000rpm, but if the regular 5.2-litre lump is bombastic, then the Performante’s motor is an early-days Prodigy gig crammed into your garden shed. I am convinced that in years to come we’ll look back at this era and wonder how an engine as visceral, tuneful and soulful as this was actually offered for sale.

Much as with the CS, we can thank time-served tuning for the V10’s additional focus, with revised intake and exhaust systems, titanium valves and the use of fluid dynamics software to improve gas-flow. Its war cry when closing in on 8000rpm must shatter fine bone china in the next county, but I also love how, in Strada mode with the exhaust valve closed, the intake rasp between 3000 and 4000rpm sounds as though the engine’s gargling with razor blades. I haven’t heard airbox music like that since the aforementioned CSL.

Performance? How about 0-100kph in 2.9 seconds, or 0-200kph in just 8.9? Even with just a delicate smear of throttle, the Performante makes its way down a road like a Cruise missile at low level, daring the driver not to brake for the oncoming corner. And, when you do, it claws furiously at the tarmac.

But what really propels the Performante to the pinnacle of this particular genre is its aero – or, in Lamborghini speak, Aerodinamica Lambo Attiva (ALA). It’s an active aero package that manipulates the flow of air for either maximum downforce or drag reduction, depending on how and where the car is travelling. It is this, along with the huge strides in tyre performance, that surely make that 6:52.01 lap time at the old Nürburgring possible. As a comparison, Sport Auto magazine timed the 360 CS at 7:56 back in 2004. Whatever else their respective merits, the Ferrari wouldn’t see which way the significantly heavier Lambo went at the Green Hell.

Back on the roads, it’s hard to judge exactly how much difference ALA is making. Certainly, the car feels very stable, but most of all it simply feels overwhelmingly fast. So colossal is the scope of the Performante’s performance envelope that it is unfeasible to deploy very much of it – or, at least, a lot of it for very long. Is this the reality of technology chasing ever-decreasing lap times? That isn’t meant as a criticism of the Performante per se, or Lamborghini even; it’s what the market seems to demand.

Thankfully, even at 40 per cent effort, a Performante is a wonderful thing. You notice the polish in its steering first – a fluid, oily quality and precision almost entirely absent from the standard Huracán. The ride in the softer Strada setting is spookily good, too.

Few things turn into a corner like a Performante hooked up with the road’s surface, such is the extraordinary front- end grip on offer, while traction, with the benefit of four-wheel drive, is massive. You can still feel the chassis working, shuffling torque, its attitude adjustable with the throttle. On the circuit, however, while the Lambo’s limits are way beyond the Stradale’s, there’s plenty of evidence that it will be a lot less tolerant once it does slide, requiring quick correction and careful balancing on the throttle. That said, and leaving the additional performance to one side, you wish every Huracán drove this well.

So Lamborghini produces arguably the world’s greatest current hardcore road-racer, though the competition with Ferrari inevitably rumbles on. There will be a harder, lighter, faster 488 GTB – we may have inadvertently seen it already. As for this pair, they’re so different but bristling with the same spirit: the Ferrari a gossamer approach to hardcore, the Performante a true raging bull in every sense. Magnifico.

This article originally appeared at evo.co.uk

Copyright © evo UK, Dennis Publishing