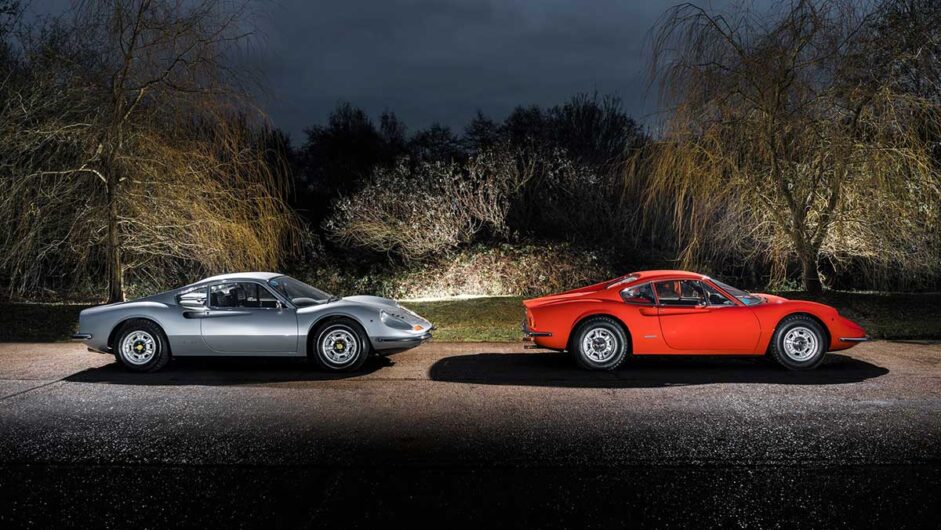

A smaller, lighter car with half the cylinders – the Dino GT was revolutionary for Ferrari. We compare original 206 with classic 246

Fifty years! Can it really be half a century? Looking at these Dinos, it seems almost impossible. In my highly partial view, Ferrari has made more beautiful cars than any other manufacturer, certainly of those that exist today; but even Maranello – or, more usually, Pininfarina – was rarely perfect. A 365GTC/4 is close, closer than the Daytona for sure, an early Boxer closer still, but, at least to me, the Dino is the only strictly street Ferrari not to be saddled with a single imperfect angle.

Let’s not dwell too much on whether the Dino is actually a Ferrari or not. At the time it was expedient for the Old Man to put a little conceptual fresh air between his new baby and the V12 titans, but it was a marketing ruse: of course the Dino was a Ferrari, as much as any other and, what’s more, better than almost all of them.

> Ferrari 250 GTO: the history, specs, prices and hype of an automotive icon

But there are two Dino road cars (three in fact, but for the purposes of this story we’re not counting the 308 GT4 2+2s) and it is our purpose today to tell their stories and identify the distinguishing features. One is, of course, the sublime 246 GT, made between 1969 and 1974, whose lineage as the staple Ferrari offering can be traced directly to today’s 488 GTB. But it wasn’t the first. That was the 206 GT, of which just 153 were made between 1968 and ’69. Finding one in perfect representative running order is hard, even if you expand your trawl to Europe, where we searched for some time before finding one right here where it was being fettled for its owner by Barkaways in Kent. Barkaways is fairly new on the Ferrari scene, but it has made the most of its six years in the market: it does nut-and-bolt restorations on site, one of which has resulted in the best 246 I’ve ever driven, itself one of nine such cars in its care. ‘We just have a lot in at the moment,’ says founder Ian Barkaway. ‘They seem to come in waves: if you’d come here a fortnight ago you’d have been falling over all the F40s we had in.

And then I saw the 206. Being a fan of old Ferraris in general and Dinos in particular, I thought I knew how it differed from the 246 it begat. Aluminium body instead of steel, 2-litre aluminium engine block with steel liners instead of 2.4 litres of cast iron. Exposed filler cap, wheel spinners instead of nuts. Turns out I knew almost nothing at all.

When today a manufacturer decides a product needs a mid-life update, the brief is always the same: make it appear as different as possible while changing as little as you can. That’s why items such as bumpers, light clusters and grilles are always being redesigned: they dramatically alter a car’s appearance without requiring the costly re-tooling required to accommodate bare-metal changes. Half a century ago, Ferrari took a different view. The 206 and 246 GTs may have names that differ by just one digit, but when the time came to turn one into the other, the brief appears to have been: ‘See how much you can change without anyone actually noticing.’

The differences are so multitudinous we’ve put them in an accompanying panel so as not to delay us unduly here. But just for a start, did you know the cars are completely different sizes and that not one panel from one could be interchanged with the other? The 206 is shorter, particularly in the wheelbase, and lower too.

It was the first road-going Dino, but not even close to being the first to bear the name of Enzo’s beloved son, who died of nephritis aged just 24 in 1956. At the time of his death he had been working with Vittorio Jano on a new Formula 2 engine for the 1957 season and it turned out to be a highly successful unit that was adapted for many sports- racing and single-seater designs, none more famous than the 246 Dino in which Mike Hawthorn secured the 1958 Formula 1 Drivers’ World Championship. It looked like a fairly conventional engine with its four overhead camshafts and heads containing just two valves per cylinder but could be told from other Ferrari V6 engines of the era by the 65-degree angle between its two banks of cylinders. Apparently this was Jano trying to ensure sufficient space within the vee for decent-sized carburettors, a move that required the crankpins to be shifted by 5 degrees to ensure even firing impulses.

> Ferrari Testarossa review, history and specs: TR generations driven back-to-back

The first sign of a Dino road car came in early 1965 and, as ever with Ferrari, behind it all lay a racing agenda. The engine was needed for another new set of F2 rules, but these also mandated that it be based on a production motor of which no fewer than 500 must be made – far beyond what Ferrari could manufacture at that time. Fiat, however, was another matter. Fiat agreed to create a new sports car called the Fiat Dino and use the engine for that. Which was one problem solved. The other was that Porsche was enjoying conspicuous success with a handy new device called the 911 and Mr Ferrari wanted a slice of the action. Now he had his production road car engine, all he needed was a car to wrap around it.

The first concept was produced by Pininfarina in time for the Paris motor show in October 1965 and all the hallmarks of the Dino’s design we love to this day – the voluptuous curves, the flying buttresses and curved rear screen as well as the air intakes carved into the doors – were already present. The following year in Turin, the styling house went one better with a Dino Berlinetta GT concept that captured the look the Dino was to adopt in all but fine detail. So when the production Dino 206 GT appeared at the same show one year later in 1967, by far the biggest change was beneath the skin, where the engine had been rotated by 90 degrees and mounted transversely behind the driver in a style pioneered the year before by the Lamborghini Miura. It made the engine horribly difficult to work on, but centralised its mass and, just as importantly, provided space for a surprisingly large boot.

It would be a flight of fantasy to say Dino Ferrari designed its engine, but its ancestry can indeed be traced back to Jano’s V6, complete with its 65deg vee angle. Its racing origins are also revealed in its immensely oversquare dimensions, with an 86mm bore and a stroke of just 57mm. No wonder it required 8000rpm on the dial before it would deliver peak power. How much power that was remains a matter of dispute: the same engine in the Fiat Dino was claimed to produce 160bhp, a stunning output for a 2-litre motor 50 years ago, but by the time it got into Ferrari’s Dino it had gained an extra 20bhp, at least on paper…

Of course, the problem with small, short-stroke engines is that they lack torque and the 206 could summon no more than 137lb ft of it, way up at 6500rpm, necessitating that power ran to the rear wheels via a five-speed gearbox filled with ratios that were as short as they were close. Keeping it all under control was a standard limited-slip differential, double unequal-length wishbones at each corner and vented disc brakes all round, setting a template that would endure in Ferraris big and small for decades to come.

The problem with the car was that it just wasn’t that quick, even for a car rather peculiarly marketed as ‘almost’ a Ferrari. In theory it would keep up with a standard 2-litre 911, though having experience of such machines, I have to say I doubt it in practice. But the Porsche was not going to stand still and Mr Ferrari realised that in order for the Dino to become a long-term success it needed to get faster for his customers to enjoy and cheaper for him to build.

> Ferrari F40 vs 288 GTO – turbocharged icons go head-to-head

Which is where the 246 GT came in. By raising the capacity of the engine from 1987cc to 2418cc (though maintaining a very high bore/stroke ratio), Ferrari was able not only to up the power to a claimed 195bhp, but also to summon 166lb ft of torque fully 1000rpm lower down the rev-range. The curious thing is that, despite the 246 being physically larger, clad entirely in steel apart from its bonnet and having a cast-iron engine block, it appears to have been only a little heavier than the 206. Published weights for these cars vary greatly but the most reliable I’ve seen suggest a 206 tips the scales at a not very sylph-like 1140kg, with the 246 just 46kg heavier. How so? I suspect the reason lies mainly in the massive steel spaceframe that, in design if not precise dimensions, is common to both. Enzo Ferrari’s decision to over-engineer the car in this way speaks a lot of his approach – his cars may not have had the greatest quality control and they certainly weren’t made from the highest-quality steel, but with his road cars just as with his racing cars, he made them strong. The truth is that some people died in his racing cars, but hardly any of them through confirmed mechanical failure.

I take the 246 GT first. Whereas I’ve never sat in a 206, its younger brother I know well. Ian Barkaway has provided an early 1970 model for the test, standard in every way save for the set of high- compression pistons he encourages owners to fit come rebuild time. ‘Everything else – cams, valves, carbs – is to original specification,’ he says, ‘but the pistons just give it a bit of extra sharpness.’

So we go through the ritual: ignore the choke and prime the three twin-choke downdraft Weber 40DCNF carbs with a few pumps of throttle. Then churn the starter with just the lightest pressure on the pedal and, without fail, the V6 growls into life. No other car in the world sounds like a Dino. The only other V6 I’ve driven that’s as melodic as this was fitted to the original Honda NSX, but the Dino’s voice is richer, more layered, more interesting if, ultimately, not quite so thrilling near the red line. I’d rather listen to it than any V8 engine Ferrari has made to date, and some of the 12s, too.

The spindly steel gearlever slots cleanly, away and back, into first. The clutch is ridiculously heavy given how little work it must do, but it takes up the power smoothly and soon we are rolling. Barkaway even has a secret gearbox mod that means you no longer have to avoid second gear when the oil is cold, though I’ve always enjoyed that particular Ferrari ritual.

We cruise at first, because you must take in the sights. I love it all: the rising curve of the wings, the grouping of the eight, beautiful Veglia dials and the unimprovable perforated Momo wheel. Even the stuff I should hate, like the stupidly offset pedals and a driving position that favours long arms but short legs, all seems to add to the character of the car. The 911 gained cult status every bit as much for the things it did wrong as right, and the Dino’s charm emanates from precisely the same place.

Temperature needles start grudgingly to heave themselves off their stops on this cold December day, warmth is percolating through the Koni dampers and I’m struck all over again by what I always forget about these cars: compared with modern supercars, a well set-up 246 rides like a limousine. These days so much secondary buzz is transmitted by tyres with liquorice sidewalls, but in the Dino on its tall 205/70 VR14 Michelin XWX rubber it’s all damped out, leaving just pure feedback to reach your fingers. And because no-one ever thought a Nürburgring lap-time relevant in a road car, the Dino is gently suspended on what would be seen as comically soft springs today. Yet it never feels sloppy; it just breathes with the road. It may be the least known of the car’s star qualities, but it is no less real for that.

Time to wind it up a little. Second gear, 3000rpm on the clock and let it go. The great surprise is that it doesn’t feel slow at all. There’s a solid surge right away, the growl becomes a snarl and you start thinking at once about how many revs you’ll give yourself before pulling back into third. I can remember as a kid gazing through the side window of a 246 GT at the tachometer and barely being able to believe that it would rev to 7800rpm. We won’t be quite going there today, but close enough to feel the car in full flight. You find yourself wanting to accelerate forever, not for the speed you’ll accrue but simply to extend time spent listening to that engine under full load. I remember wondering whether it would be more accurate to describe it as ‘addictively exquisite’ or ‘exquisitely addictive’ and decide on the latter. It is a sound of which no true enthusiast could ever tire.

Sooner or later, however, you need to slow and climb back down through the gears. The brake pedal is a little mushy on this car, making heel-and-toeing difficult, but there’s no snatch in the driveline and the gearshift, while quite slow and heavy, is deliciously clean. There are corners ahead and something in my brain reminds me from years back how the car should feel: the steering should weight up almost immediately, become flooded with feel long before the suspension is fully loaded, and guide the nose into the apex with unwavering accuracy. The car should be alive, on its toes, ready to change direction at zero notice. And it feels all those things. To guide a 246 through some curves, nowhere near the limit but just feeling it talk to you, is a rare and special experience, even in a Ferrari. Offhand, and of them all, I’d say maybe only an F40 is more communicative than this. I know what Dinos do on the limit, too: they choose to understeer a little, but this can be cancelled by the merest lift of the foot or transformed into equally gentle oversteer by the sudden reapplication of power. Unlike the other Ferraris of the era with which it had to share stable space, the Dino is probably even stronger in the corners than down the straights.

What, then, would the lighter, smaller and presumably more nimble 206 be like by comparison? Well, I had to get into the thing first. Unlike the 246, it has a large wooden-rimmed wheel and, as with all 206s, it’s on the left-hand side of the car. I just managed to thread my legs around it, only to discover I could barely select first gear. Headroom was somewhat tight, too. But I was in, and not about to be deterred.

I don’t know why, but while I knew it would be slower, I nevertheless expected the 206 to offer a sharper, more aggressive driving experience. I’d clocked the 8000rpm red line, seen its four pea-shooter exhausts and imagined its all-alloy engine to be even closer to a race motor. Not so. I’d not say it sounds completely different to the 246, but its voice is smaller, sweeter, very much the junior sibling.

It feels a little odd at first, largely I guess because what you notice are all the differences to the 246 – the still shorter gearing, the lighter steering and, most of all, the lack of power. Even with the high-compression pistons, while it is smooth and uncomplaining at low revs, there’s very little shove. It starts to build from 4000rpm – just half way to the red-line, remember – and while I ventured a little higher, I had promised its owner I’d not stress his newly rebuilt motor. I suspect that were you to wang it around to 8000rpm you’d see a completely different side to it: the gears are close enough to keep the engine on the boil and I’d not worry about damaging it at all. Indeed, all the folklore about this engine and that in the 246 is that you’re much more likely to harm it by treating it gently and never letting hot, thin oil properly circulate the top of the motor. Up there I expect its racing origins to be most obvious and the car’s character more evident.

Even as it is, the 206 feels a little more highly strung than the 246, less comfortable and slightly more antiquated to drive despite the fact that the two are separated by just a couple of years.

Then again, Enzo was trying something completely new with the Dino: not just his first mid-engined road car, but the first of an entirely new kind of Ferrari so it’s no wonder that the learning curve was steep at the start.

The 206 GT is the purer of the two, with its ally body and block, slightly lighter weight, more compact dimensions and an engine even more keen to scream. If you want the clearest image of Enzo Ferrari’s vision of a road car worthy of his son’s name, it’s the one I’d advise you to drive, if you could ever find one.

Otherwise, the 246 is better in every way: quicker yet more practical, more entertaining yet more comfortable. To be on board, looking at the cabin and the view ahead, feeling the steering and hearing that V6 howling its inimitable song remains one of the greatest pleasures ever afforded a motoring enthusiast. Just because it lacks the name, never mistake what this car really is: the finest Ferrari production road car with fewer than 12 cylinders.

Key differences

Here we try to pin down the differences between a Dino 206 GT and a 246 GT. As with many things Ferrari in the 1960s and 1970s, this is not an exact science, with some early 246 GTs carrying over some or more of the features of the 206 GT.

Note: no Dino left the factory wearing Ferrari badging. However, it is not entirely wrong for Dinos to wear them… importer Maranello Concessionaires equipped many 246s with both a Ferrari logo above the number plate and a prancing horse to one side.

| 206 GT | 246 GT | |

| Length | 4150mm | 4235mm |

| Width | 1700mm | 1702mm |

| Height | 1115mm | 1143mm |

| Wheelbase | 2280mm | 2340mm |

| Weight | 1140kg | 1186kg |

| Engine cc | 1987cc | 2418cc |

| Bore x stroke | 86mm x 57mm | 92.5mm x 60mm |

| Carburation | 3 x Weber twin choke DCN14 | 3 x Weber twin choke DCNF |

| Compression ratio | 9.3:1 | 9.0:1 |

| Engine power | 180bhp at 8000rpm | 195bhp at 7600rpm |

| Engine torque | 137lb ft at 6500rpm | 166lb ft at 5500rpm |

| Specific output | 90.6bhp per litre | 80.6bhp per litre |

| Power to weight ratio | 160bhp per ton | 167bhp per ton |

| Body construction | All aluminium Steel, with aluminium bonnet | |

| Engine construction | All aluminium Cast iron block, aluminium heads |

This article originally appeared at evo.co.uk

Copyright © evo UK, Dennis Publishing