Our man on the ground is given an insight into the Bloodhound Supersonic Car, which – if all goes well – WILL be the fastest car on the planet.

[Not a valid template]In the past decade, it’s become easier than ever to be blasé about fast cars. Today, a 500bhp output is unremarkable. Top speeds above 320kph aren’t unusual; they’re expected. Hitting 100kph in less than three seconds is something that happens all the time. But there’s a project under way that will quite literally redefine what a fast car is. It’s called the Bloodhound Supersonic Car (SSC), and it’ll be the fastest car ever built.

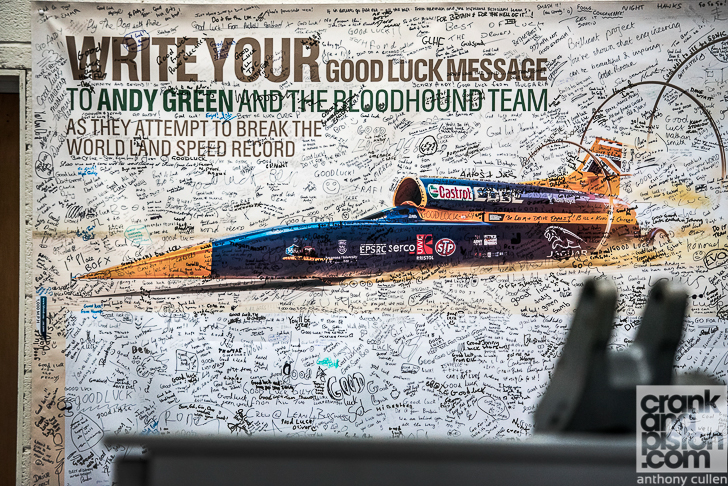

Bloodhound is an enterprise that will see a genuine, bona fide car – four wheels, steering wheel, driver’s seat – hit 1000mph, or 1609kph, on land. It’s an undertaking that makes the best efforts of Bugatti and Bernie Ecclestone seem frankly piffling, with power coming from a fighter jet engine and rocket motors usually used to send satellites into space. Bloodhound, which runs out of an unassuming warehouse near Bristol, UK, is pushing automotive technology way beyond the bounds of our previous experience. And yet, designing, building and driving the fastest machine on land isn’t actually the main aim of the project. Bloodhound exists mainly to inspire a future generation, explains the project’s chief engineer Mark Chapman.

“The primary goal of the project is kids,” Mark says. “Our target audience is eight- to 12-year-old children, to basically make them think that science isn’t rubbish. And the reason that’s come about is there is a massive shortage of engineers. It’s not that we necessarily need a whole generation of supersonic car designers, but you do need a lot of people to do renewable energy, automotive stuff, aircraft, infrastructure, roads, everything and they need people that are excited by science.

“If I show my nine-year old daughter a car that goes a bit slower than a Formula 1 car, but is powered by sunlight, the kid goes: ‘But that goes a bit slower than that car over there, and it’s really quiet, and it’s not as exciting.’ Whereas this thing; it’s got 135,000hp, 20 tonnes of thrust, it’s got 60 feet of flame out the back, and when it drives it’ll be the loudest noise on planet Earth. If you’re a ten-year-old kid, that’s cool.”

Mark has been involved since the project’s inception in 2007. A trained aeronautical engineer, his focus before Bloodhound was the Joint Strike Fighter aircraft, also known as the F-35 Lightning II. He’s therefore very familiar with making machines go fast, although not necessarily without taking off. For all the school liaisons and educational work that Bloodhound is doing, breaking the land speed record of 1227.985kph (763mph) remains a high priority. He wants it to inspire as the Apollo space programme or Concorde did.

The existing record was set in 1997 by Thrust SSC, a car piloted by the same man who’ll drive Bloodhound – Wing Commander Andy Green of the British Royal Air Force. There isn’t a vast pool of experienced supersonic car pilots, but it’s safe to say that regardless, Andy is one of the best. But his skills at catching drifts at more than 1000kph will be nothing if the car isn’t up to it, and there’s a team of 80 people that have come up with the car’s cutting edge design. Unlike Thrust SSC, which was theorised, built and then analysed, Bloodhound was first constructed virtually, using all the computer power available in the second decade of the 21st century. Computational fluid dynamics, and numbers crunched by a supercomputer, let designers know how their ideas will react aerodynamically, and the software can even optimise particular parts before they exist in reality. Such technology is vital on a project where the smallest mistake can be catastrophic. There are very few guidelines or templates to be drawn from, so every single aspect has to be considered.

“It’s got to be driven. The wheels have got to stay on the ground. And it’s got to do two runs in an hour,” says Mark Chapman. “And that’s it. Everything else is up to you.

“Thrust SSC wasn’t six men in a shed knocking something out, but it was more at that level. With Bloodhound, because the forces are so great, you can’t really do that design, build, test, refine process. It isn’t ‘let’s just put a bigger jet in to Thrust SSC and see how it goes’. That step from 800 to 1000mph is a huge leap.”

After years of work, the end is in sight, with testing at slower speeds due this year before the record attempt in 2017. Now close to full assembly, Bloodhound sits, silent and foreboding, in the middle of the project HQ, surrounded by spare parts and assorted machinery. It’s almost hard to comprehend what it’s capable of, as it looks like almost like a very large model; a child’s idea of a rocket for the land. Mark describes it as less of a supersonic car, and more of a supersonic truck – it weighs in at 7.5 tons. When we visit, the three Nammo rocket motors at the back are missing, but the EJ200 jet engine – as found in the Eurofighter Typhoon – juts out the back, above a surprisingly simple looking rear end. Because the car’s power comes from thrust rather than an engine, there are no drive shafts and the huge aluminium alloy wheels – clad temporarily in rubber for upcoming test runs – sit free.

Beneath the massive air scoop is the cockpit, accessed by dropping down through a hatch and into a carbon fibre race-style seat. A mock up of the removable steering wheel, custom made to suit Andy Green’s surprisingly large hands, sits on the seat while to the left and right are consoles of Rolex-made dials, switches and levers. It looks surprisingly low-tech, like a cold war jet fighter, but in front are three full-colour screens that show speed and when to deploy the different braking methods. Huge air brakes will be hydraulically deployed from its flanks to slow the car down, so that parachutes can then be released. The huge steel brakes only come into effect at around 250kph. Carbon discs weren’t used, as the G forces at 1600kph would blow them apart.

Panelling on the left hand side of the car has been removed to let visitors glimpse beneath the surface, which is surprisingly spacious – there’s no extraneous clutter and weight under the skin. Behind the cockpit sits a huge 800-litre fuel tank for the rocket motors, which will be emptied in 50 seconds by a modified, supercharged, 5-litre Jaguar V8 engine. Kitted with a dry sump and driven by a custom chain-drive transmission, it’ll instantly rev to 10,000rpm, using 600bhp to flush 40 litres of fuel per second into the rockets.

Although many aspects of Bloodhound are forged through the highest technology available, other bits are pleasantly low-fi. The triggers on the steering wheel that fire the rockets are taken from a hand-drill – as Chapman points out, that’s well-proven technology, so why reinvent it? The bottom of the car features rivets all put in by hand. The curved aluminium sheets on the car’s fin are hand rolled on an English wheel – the same technology used to create the bodywork of a Jaguar E-Type – because custom tooling would be prohibitively expensive and largely pointless unless Bloodhound becomes a production vehicle. Currently, there are no such plans.

Several test runs are organised over the next year so that engineers can shakedown Bloodhound at increasing speeds, from 320kph up to almost 1300kph. Assuming all goes to plan, the record-breaking run will take place in 2017 at the Hakskeenpan Pan in northern South Africa, close to the border with Namibia. Because the immense speeds involved, the surface has to be perfect, as the slightest imperfection, stone or crack could have catastrophic consequences.

Preparing the track has become a major project in itself. The Bloodhound effort has employed 300 people in one of the poorest parts of South Africa to painstaking clear a stretch of desert that equates to a dual carriageway between London and Moscow. A stone in Bloodhound’s path could be fire into the car with ridiculous force, so it’s essential that the track is smooth and some 16,000 tones of stones have been removed. The result is a course 17km long and 2.4 km wide, which will allow for around 20 attempts – once a section of track has been used, it can’t be run on again.

If all goes well, Andy Green will pilot Bloodhound to its ridiculous speeds within two minutes. Mark Chapman gets visibly excited as he looks forward to the attempt. “The 0-100kph time is so rubbish we don’t even talk about it,” he grins. “We do 0-100mph (161kph) in around 15 seconds, whereas a Veyron will do it in about eight. But we do 0-1000mph (1609kph) in something like 30 seconds. Your blink reflex is a fifth of a second, so if you sat in a football stadium it would come in one side and go out the other while your eye was closed during the blink. It would cover four and a half football pitches a second. It’s like having a fire engine with guys and all their kit in that goes as quick as a Formula 1 car.

“Things like that are what gets kids excited. And grown ups too.”