Famously victorious at Le Mans in 1988, Jaguar’s XJR-9 ended Porsche’s dominance during sports car racing’s golden era

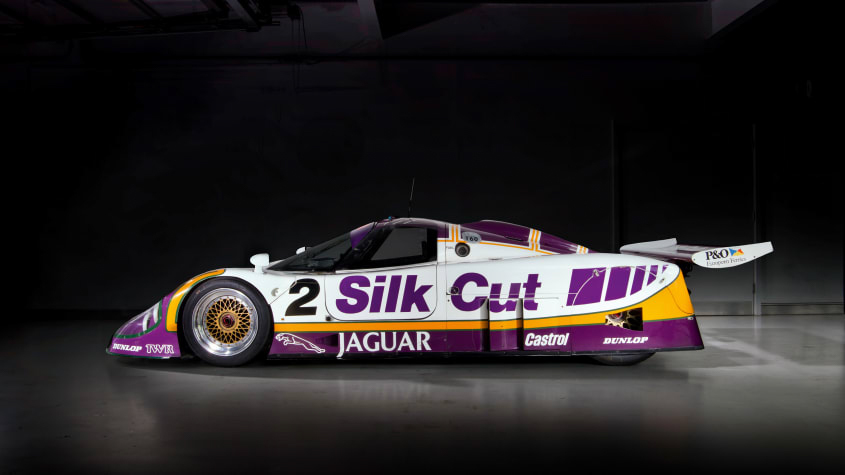

For many, the Group C decade of international sports car competition – 1982-1992 – was the last great era of sports car racing. A time when up-and-coming F1 stars still took busman’s holidays to drive brutal sports cars for the cash and the hell of it, and when the best circuits combined romance and danger, such as the Nürburgring Nordschleife (just) and a pre-chicane Le Mans. But most of all we remember the cars: big, bad, monstrously powerful prototypes. Our featured car for this ‘Anatomy Of’ story is one of the mightiest of them all: TWR-Jaguar XJR-9LM chassis no. 488, winner of the 1988 Le Mans 24 Hours.

The birth of Group C

Group C had its roots in a class devised by the ACO (the Le Mans organising body in France) for 1976. Called ‘Le Mans GTP’ it was for closed-roof prototypes with a set fuel allowance and it sat within an already complex rules structure (there were nine separate classes at Le Mans that year). Also new that year were FIA rules regarding top-level sports car racing.

Groups 5 and 6 respectively were for wild-looking silhouette versions of production cars (think the 911-based Porsche 935) and open-roof prototypes (such as the Porsche 936, which won Le Mans outright that year and in 1977 and 1981 too). In time, they failed to attract a broad entry of manufacturers, so during 1979-1981 new formulas were developed by the FIA as part of a radical shake-up of every aspect of motorsport. The result was the Group A, B and C regulations, the last of those three aimed at prototype sports car racing. Group C was essentially a fuel consumption formula, with 60 litres of 102 RON racing fuel per 100km the theoretical maximum consumption, fed by a tank no larger than 100 litres and, initially, with no more than five fuel stops allowed. Races were originally long-distance battles, over 1000km, thereby meaning 600 litres was the maximum amount available for the total race distance, but these were shortened in the interests of TV later in the decade. At Le Mans, a total of 2600 litres was initially available, but all these fuel provisions were reduced over the years of Group C, and not without predictable controversy amongst entrants.

The beauty of the regs was the open-ended section on engine choice. Of course, there were various minimum and maximum dimensions for the cars, and a minimum weight limit (800kg initially, 850kg from 1985), but as long as an engine was from a manufacturer already participating in Group A or B, it was eligible. That effectively meant engines derived from production car units, which gave not only variety but also a strong marketing link for big brands with healthy budgets to spend in an era when technical advancement and furthering car sales were both inherent to motorsport participation.

Porsche initially dominated with the 956, which crushed the fast but fragile Lancia LC2s and the short-lived Ford C100. Jaguar then arrived part way through 1985 with Southgate’s first iteration of the XJR series, the XJR-6, and soon rose to ascendancy, surpassing the ageing 962C (the 956’s successor) and winning the World Championship in 1987 and 1988. That year Porsche withdrew its factory squad from the series – the ‘works’ appearing only at Le Mans – and the Sauber Mercedes team became the new threat to Jaguar. By the following year, with overt backing and technical assistance from Mercedes, the new ‘Silver Arrows’ of Sauber won the Le Mans 24 Hours, the Drivers’ and Makes’ titles.

The series had reached its zenith, with numerous privately entered Porsches, plus works teams from Toyota, Nissan and Mazda, as well as Aston Martin. Yet dark clouds loomed, and the rules were changed for 1991 with the advent of 3.5-litre naturally aspirated engines only – in line with F1. Those lighter, high-downforce cars were as dramatic as they were ill-fated, and lasted only to the end of 1992 (with one more year at Le Mans), so it’s the original 1982-1990 Group C formula we’ll concentrate on here.

Chassis 488

TWR (Tom Walkinshaw Racing) that seized victory from Porsche at Le Mans in 1988, chassis 488 was crewed by Jan Lammers, Johnny Dumfries and Andy Wallace. After winning a terrifically close-fought contest it was immediately given to Jaguar Heritage Trust, where it has remained since. Our guide here is the car’s designer, Tony Southgate (also designer of BRM, Shadow and Arrows F1 cars, the Ford RS200 and many more besides), with driving impressions provided by Wallace.

Chassis and aerodynamics

‘Tom [Walkinshaw] took me around the workshop, and said: “The brief is you can do anything you like as long as you use that V12 engine,”’ recalls Southgate today. ‘I’d never seen such a big engine – it’s colossal! Although it was single cam it had bits sticking out all over the place, and it was very heavy, so I thought: “That’s going to be a challenge.” That was the end of 1984, and we were racing from the second half of 1985. I had to make the best car I could with that package. It took a while to refine, but it showed promise straight away.

‘The opposition was Porsche, and they were incredibly reliable – that’s the tricky bit – but they did have weak areas. Although the car looked very trick aerodynamically, and very sleek – they were obsessed by long tails, very Germanic – I could tell that they weren’t producing high downforce because the front wasn’t the right shape, it was just preparing the air to go under the car nicely and over the rear wing. I benefitted from the wind tunnel work I’d done on the [stillborn] Ford C100 Mk3 at the London Imperial College wind tunnel with its rolling road. Someone had told me Porsche’s wind tunnel road was fixed, so I knew their info on centre of pressure could be up to 15 per cent out.

‘At Le Mans we had to beat the Porsches on the straights. I knew what horsepower we’d got, so I whittled the drag of the car down until it achieved a theoretical 386kph on the straight – the Porsches did 378kph – and worked back from that. Then I said, “What’s the maximum downforce I can get with that drag?” Hence the chopped-off tail. Porsche always had long tails; they couldn’t comprehend that you could have a car with a short tail [at Le Mans] – they were utterly mystified. They’d come up and stare, and even ask me, “Does it really work like that?” They didn’t realise the rear wing was effectively an extension of the body. The gap is like the slot you get in a wing, so it bleeds underneath, at the same time pulling air out from the venturi.’

The layout of the Porsche’s boxer motor also interfered with the ground-effect tunnels under the car: ‘The most you can go up on a venturi is 11 per cent before it starts to stall, but if you have a wing on the back pulling the air through, like the “9”, that’s critical – you could go a much steeper angle without it stalling. Porsche couldn’t do that. Although they angled their engine and ’box, it was nowhere near as good as proper venturis. I could really exploit that area.

‘They also had a very flimsy monocoque. It wasn’t even aluminium honeycomb, just aluminium box-section. It looked very robust from the outside, but wasn’t strong. I went for a full carbon chassis so we had an incredibly stiff structure, and the car was always on the weight limit even with that bloody big engine.

‘I had to get it as far forward as possible, so it was right up to the driver’s shoulder, recessed into the bulkhead to get the weight forward, and then a long bellhousing to the back axle. The weight of the engine, and the high C of G of it, always dominated the car, so you needed good roll stiffness. We ended up with a lot of downforce, which made up for any weight distribution [40:60 front-to-rear] deficiencies. We always had about 40 per cent aerodynamic pressure on the front, whereas Porsche had about 25 per cent at best.’

The Le Mans cars were very different to the ‘sprint’ cars used for the rest of the season: ‘We had a Le Mans aero package: a different nose with no front splitter, a different tail and underwing. The wheelarches were shaved to the minimum for Le Mans to keep the frontal area down. Under braking the tyre almost touched the body because of the downforce. The body was very close to the tyre, and this gave a better airflow to the rear wing.’

What Southgate and TWR created was an all-carbon, high-downforce package that was a huge step on from the Porsche. ‘If you have a stiffer structure, the suspension responds much better to any changes. Porsche couldn’t run really stiff springs as it just twists the chassis.’ It’s no surprise that most of the rival cars that followed looked a lot like an XJR Jag.

The engine

One of the reasons Porsche dominated the series in the early years was that its twin-turbo air/water-cooled flat-six had already won Le Mans in 1981, fitted in a 936. Not only was the new 956 fast, it was monotonously reliable, in the main, and with Porsche’s policy of selling cars to anyone with a large enough chequebook, it was numerically superior too.

TWR was experienced in racing Jag’s V12, having won Touring Car titles with the XJ-S. When Southgate’s XJR-6 arrived part-way through 1985 it used a 6-litre version of the engine with 600-650bhp, later rising to 6.3 and 6.5 litres during 1986. It grew to 7 litres and around 700bhp for 1987’s XJR-8, and was retained for 1988’s XJR-9 and used at Le Mans in 1989. The ultimate V12-powered Jag was the XJR-12, purely for Le Mans in 1990/1991, powered by a near-750bhp, 7.4-litre evolution.

The naturally aspirated ‘12’ had its good and bad points. Positives were its tractable, good-natured delivery from low revs, and its smoothness – kind on ancillaries and minor components during 24 hours of racing. Fans adored its guttural, terrifically loud roar. Its narrow V angle also enabled enormous venturi tunnels under the car, but accommodating the size and weight of the engine was a challenge, and its high centre of gravity impacted handling. In performance terms, while the Porsches originally had around 620bhp at Le Mans in the turbocharged 2.6-litre 956, that grew to 700bhp+ in later 2.8 and 3.0 versions of the related 962C. More boost could be run in qualifying, a luxury the Jags didn’t enjoy, then reduced for more fuel-efficient running in races.

The Jag’s downfall was the rapid development of the Sauber Mercedes, powered by a twin-turbo 5-litre V8, a low-stressed, low-boost, economical solution, yet able to create enormous power in qualifying spec. ‘We ended up building a turbo engine in desperation,’ rues Southgate, referring to the 3.5-litre V6 twin-turbo Jaguar XJR-11.

Driving the ‘9’

‘It was quite a short wheelbase and the engine was high up,’ recalls Andy Wallace, ‘and if you got it out of shape you’re essentially shutting the venturi tunnels off, which further reduces grip. However, the faster you go, the more it squats at the back as the centre of pressure moves rearwards, and that promotes understeer so the rear is less likely to step out.

‘You had to be a bit wary of the front in high-speed corners, actually. You could easily break a driveshaft in them: the March-sourced dog ’box was the weak point. At Le Mans we’d run a solid rear diff, so you’d brake into a slow-speed corner and then get on the gas and steer it on the throttle. There was no power steering so it really loaded up in high-speed corners, but it did stop well – the massive downforce helped there, too. You had to push the pedal hard, but they were very linear, not like carbon brakes. You had to drive it aggressively to drive it fast, not like a modern car.

‘Drag at Le Mans is the number one enemy, but Tony was brilliant. The best of the Porsches [in ’88] probably had 50bhp more, and they’d come past leaving Tertre Rouge and onto the Mulsanne. But then every lap a little further on the straight I’d repass them, which they didn’t like at all. 5.5 kilometres, flat out, for 50 seconds, at nearly 402kph. I was 27. You have a small imagination then.

‘That blue box on the dash let us know the fuel situation, but the lights in each corner are for monitoring the tyres. The radials couldn’t cope with the speeds on the Mulsanne so we ran crossplys, but they grow at high speed, and when they let go there’s only a small vibration, a slight drop of revs, and then BANG!, flailing rubber and you’re upside down at over 322kph, which happened to Win Percy in 1987 in an XJR-8. So we had infrared heat guns pointing at each tyre in three places, and if they got hot the corresponding red light would flash on that box. You could then press it to read the temp. Win had the system in ’87 but it wasn’t working properly in the rain.’

Percy’s accident is one of the most spectacular crashes ever survived by a driver, and involved multiple barrel rolls above the treeline. The Jaguar’s immensely strong carbon tub meant he walked away with just a bruised knee. ‘Win would have been dead if he’d been in a Porsche,’ says Southgate bluntly. Indeed, three world-class drivers were killed in Porsches during the Group C era.

Later, TWR acquired the Metro 6R4 engine from Rover and turbocharged it, but there were only two years of the formula left to run and it was always trying to catch up. Still, the 3.5-litre V6 twin-turbo XJR-11 remains one of Wallace’s favourite cars.

‘In the race we’d have up to 820bhp, but in qualifying as much as 1100bhp – in an 850kg car! It was only mapped for idle, quarter throttle and full throttle, it wasn’t driveable at all – lots of lag, really quite scary. It would stretch the head bolts and let all the water out, so we’d run it at 900bhp with a 200bhp overboost button. On heated qualifying tyres you’d get one out lap and then nine corners in both directions and then that was it.’

Postscript

It’s commonly believed that Messrs Ecclestone and Mosley and the autocratic FIA president, Jean-Marie Balestre, didn’t want Group C to rival Formula 1’s dominance. Their switch to what were effectively F1 engines for 1991 was a disaster, and the 1993 championship was cancelled before it began. Even now, sports car racing has yet to fully recover.

But none of the 50,000+ British fans who crammed into Le Mans will forget that emotional 1988 victory. Jaguar could surely use a sprinkling of 488’s winning magic right about now.

This article originally appeared at evo.co.uk

Copyright © evo UK, Dennis Publishing