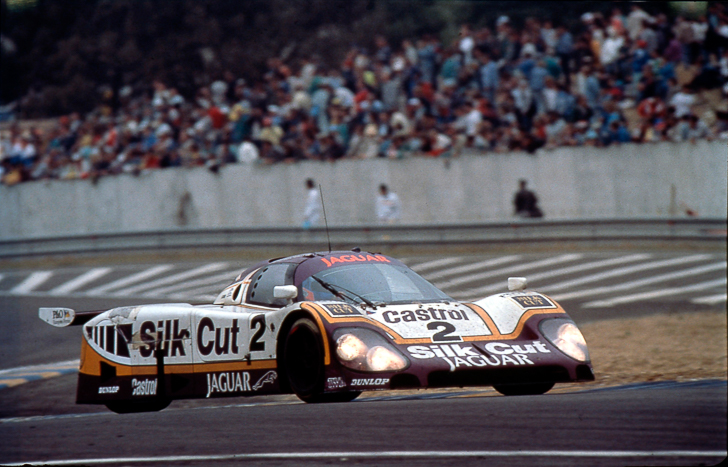

It’s not every day you get to sit down with a winner of the 24 Hours of Le Mans. But when Jaguar launched the revised XJ at Silverstone in the UK, it seemed like a good opportunity to show off the iconic Jaguar XJR9 LM, winner of the 1988 Le Mans race. And it would be a shame not to bring along a driver too…

British racer Andy Wallace was part of the team that drove the XJR9 LM to victory at the Circuit de la Sarthe, and went on to a stellar career in sports cars. Luckily for us, it’s a career he’s very happy to reminisce about.

[Not a valid template]Andy, let’s start with the XJR9LM. It was yours and your colleagues to command at Le Mans, and it finished, and then it was put in a box.,.

“Yes, it was me, Jan Lammers and Jonny Dumfries. That particular chassis – number 488, which was built at the beginning of 1988 – did a couple of races and didn’t finish a single one before Le Mans. Le Mans is the only race that car ever won.

“At that point Ford were about to take over Jaguar, so at the end of the race they sold the car to the Jaguar Heritage Trust, to get it out of the system and make sure that it wasn’t lost. So it still belongs to the Heritage Trust.”

How often are you reunited with it?

“Well, this is the fantastic thing – when I stepped out of it after Le Mans, you don’t think about when you’ll drive it again because you’re busy racing. As time went by I was asked a few times by Jaguar to drive up the hill at Goodwood and it was fantastic to be reunited with it. It was probably 10 or 12 years after the event before I drove it again. Since then I’ve done various other events driving it around proper race tracks, which is fantastic.”

Looking back, what were your initial impressions of the car and sports car racing, before Le Mans?

“Jaguar was going to Le Mans that year, 1988, with five cars. Mine was the number two car and the three drivers had to get together and agree how we were going to challenge the race. In those days the gearbox was incredibly fragile, as was the engine – there were no real rev limiters, so if on downshifts you hooked the wrong gear, then BOOM! It didn’t take much. 1000rpm above shift point on a downshift would break a valve spring.

“Le Mans is the pinnacle of sports cars so if you get a chance to race at that level, generally what’s happened is that you’ve come from one of the single seater categories. In single seaters you have to be incredibly selfish and trust no one, and then suddenly you’re thrown into this arena where there are three drivers and to win, you need to trust each other. It’s an alien thing. I came straight from Formula 3 and had no experience of sports car racing – Le Mans was my third race.”

Having been ‘incredibly selfish’ in single seaters, was the transition to sports cars particularly difficult?

“Well, Jan Lammers was the team leader and could see I needed some help with what to do. We all sat together and went through everything that could go wrong, and talked about what we could do to make sure it didn’t. These days, you put fuel in the car, send it out and drive it absolutely flat out over the kerbs, bounce off the slow cars, bring it back in as a steaming pile, shove tyres on it and send it out again. And it’s fine.

“In those days, 900kg was the minimum weight, so the cars were made very light, but they had to be fast and durable at the same time. There were weaknesses. The engine was built on the Jaguar V12 production line – it was essentially a road car engine – so it was a bit fragile at those speeds, especially as it was tuned up to nearly 800hp. The engines had so much torque that the gearbox got an absolute hammering. Probably 60 or 70 percent of retirements then were due to broken gearboxes. Now it’s all pneumatic paddle shifts, so you can’t select the wrong gear, but in those days you were doing it yourself. If you’re got a corner that’s borderline third or fourth gear you can go through in third with lots of revs, maybe half a tenth quicker, but if you go through in fourth it’s one downshift and one upshift less on a whole lap. Multiply that by 361, which was how many laps we did in the race. And that’s a lot. It’s good management, because you can make the gearbox last. We did that in several places, but in order for it to work you’ve all got to trust each other and all be on the same programme”

That must have been a bit of a culture shock…

“It was. I’d won the British F3 championship and couldn’t afford the money to go to Formula 1, so I was in a bit of a no man’s land and didn’t know where to go.

“At the end of 1986 all the successful Formula 3 drivers congregate for the Macau Grand Prix. It’s a big deal and some of the F1 drivers used to do it too. Jan came back to do it and I was there too. I won the race and Jan was second. We were chatting on the podium, and he asked what I was doing the next year, so I said nothing. He had a word with Jaguar and they needed one more driver for Le Mans. I was invited to Paul Ricard Circuit in the south of France with a few other guys, passed the audition and got the drive.

“It was Jan that got me the drive and I trusted him 100 percent. I just had the feeling that he wasn’t going to try and pull one over on me. He could have told me to drive corner X slightly slower, and then by the end of the race he could have been faster and been a superstar. You do that in single seaters, but you can’t do it in a sports car, you all have to pull together.”

What was the car like to drive after your single seater experience?

“I’d driven cars up to around 180mph (290kph) before – today quite a lot of road cars will go that fast, but in the day they were nowhere near. So for me 180 was fast but I could deal with it. From that, to jump in the XJR9 – it’s capable of 240mph (386kph), and that jump is huge. This was before the chicanes on the Mulsanne straight so it’s staggering how fast you’re going, and it doesn’t seem to end; you just keep getting faster. It’s 5km, the straight at Le Mans, and it took 50 seconds of full throttle to travel. It’s incredible.

“In the slow and medium speed corners you’re more reacting to the dynamics of the car rather than the aerodynamics. But because the downforce goes up as a square of the speed, and you’re doing more than 240mph (386kph), the amount of ride height you lose is huge as it’s dragging itself into the ground. You have to run monster, ridiculously heavy springs to not grind itself away on the straights. But that means when you arrive at the corners you’re way oversprung, don’t have any downforce so the car was very skittish.”

How did the XJR9 compare to the sports cars that you drove subsequently?

“Well, the rules keep changing. Every time the rules change, the cars are very different. The XJR9 just blew me away because of its speed. It was new to me, but after that we had XJR11 which was the V6 twin-turbo car with more downforce and more power, and in qualifying we had 1100 horsepower. That made the XJR9 feel almost slow. Finally the rule change saw the 900kg rule go away, so cars were 750kg and used 3.5-litre V10 Formula 1 engines, and that’s what killed Group C unfortunately, because it was too expensive. When you first drive one of those cars, you’re suddenly cornering so much faster. They were still ground effect, had almost double the downforce and were 150kg lighter. It was unbelievable.”

What do you make of sports car racing today?

“I think it’s really exciting, because it’s still, more than F1, a platform where you can try out technologies that are more relevant to road cars. Headlights for example – if you see the development at Le Mans it’s unbelievable. We had the shittiest lights but now it’s at the point where it’s daylight, and you can really gain speed if you can see where you’re going. The hybrid systems that they’re using in a sports cars have a lot more freedom than in F1 and they’re much more road relevant. I think you’ll see a lot of those Le Mans systems appearing in road cars in the not-too-distant future.”

As a former event winner, any idea who might take Le Mans victory in 2016?

“The manufacturers – Toyota, Audi and Porsche to some extent – are all going at it differently. One’s got a six cylinder engine, one’s got an eight, one’s got a four, some have got two electric motors and some have got one, some have got lithium-ion batteries while others have flywheels, one uses supercapacitors. They’re all coming at it from different angles and the cars are staggering, so it’s really difficult to call.”