Concerned about the environment but aren’t yet ready to give up vehicles containing two and half tons of raw materials and interiors featuring more leather than a branch of Doc Martens? You probably aren’t the only one as it turns out, as Land Rover will now sell you the Range Rover P400e PHEV – a plug-in hybrid variant of the full-size Range Rover, available in both standard and long-wheelbase formats.

Any environmental kudos will probably be moot next to the potential taxation and usage benefits of a plug-in Rangie for the brand’s typical customers, but to make sense it must also feel like a proper Range Rover – and when the primary source of power is a 2-litre, four-cylinder engine, that’s not as easy as it sounds. So does it succeed?

Engine, transmission and 0-100kph time

No six- or eight-cylinder unit here; beneath the Range Rover’s considerable clamshell bonnet lies a 1997cc inline four-cylinder “Ingenium” petrol engine. Use of such a lump means that in JLR’s entire catalogue only the XJ and the new all-electric i-Pace do not yet boast a four-cylinder engine somewhere in their respective lineups.

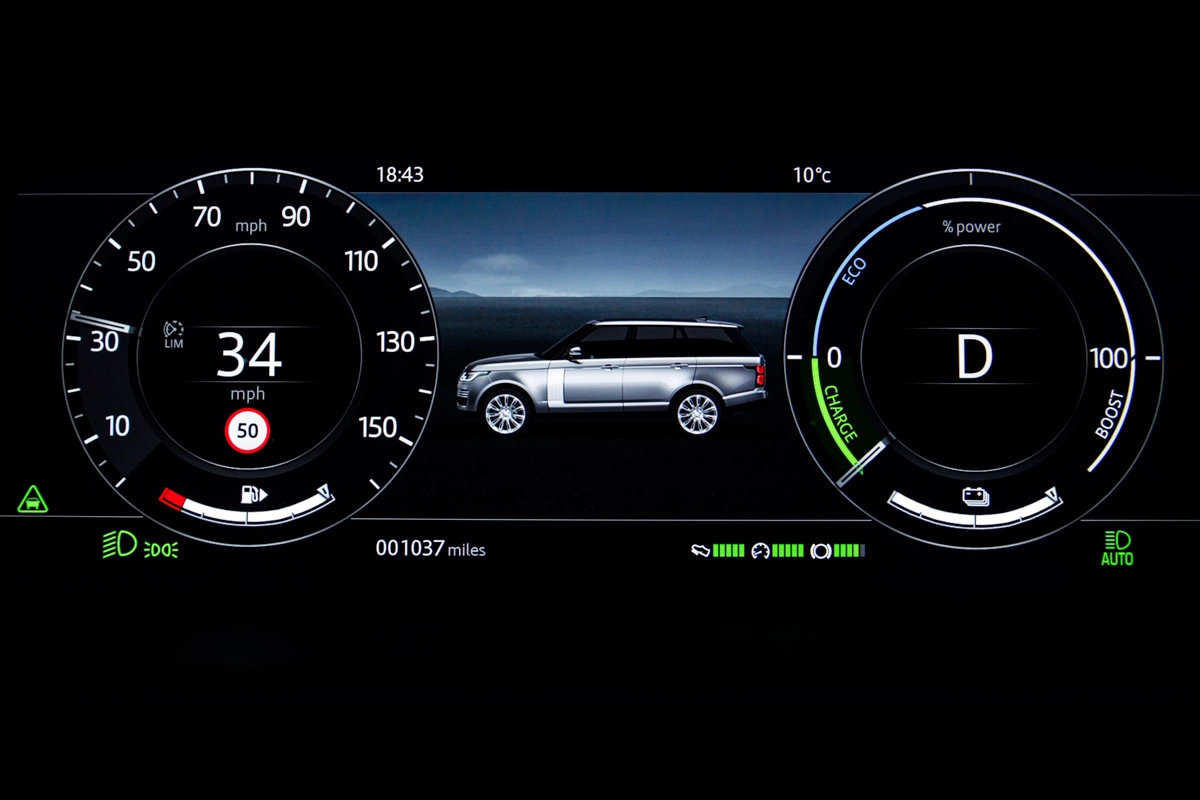

In this format the Ingenium develops 296bhp on its own, a figure raised to 398bhp when the efforts of a 114bhp electric motor sandwiched between the engine and transmission are taken into account. Peak torque is quoted as 472lb ft – in the Range Rover lineup that gives it more twist than the V6 diesel or supercharged V8 petrol, but less than the 4.4-litre V8 diesel.

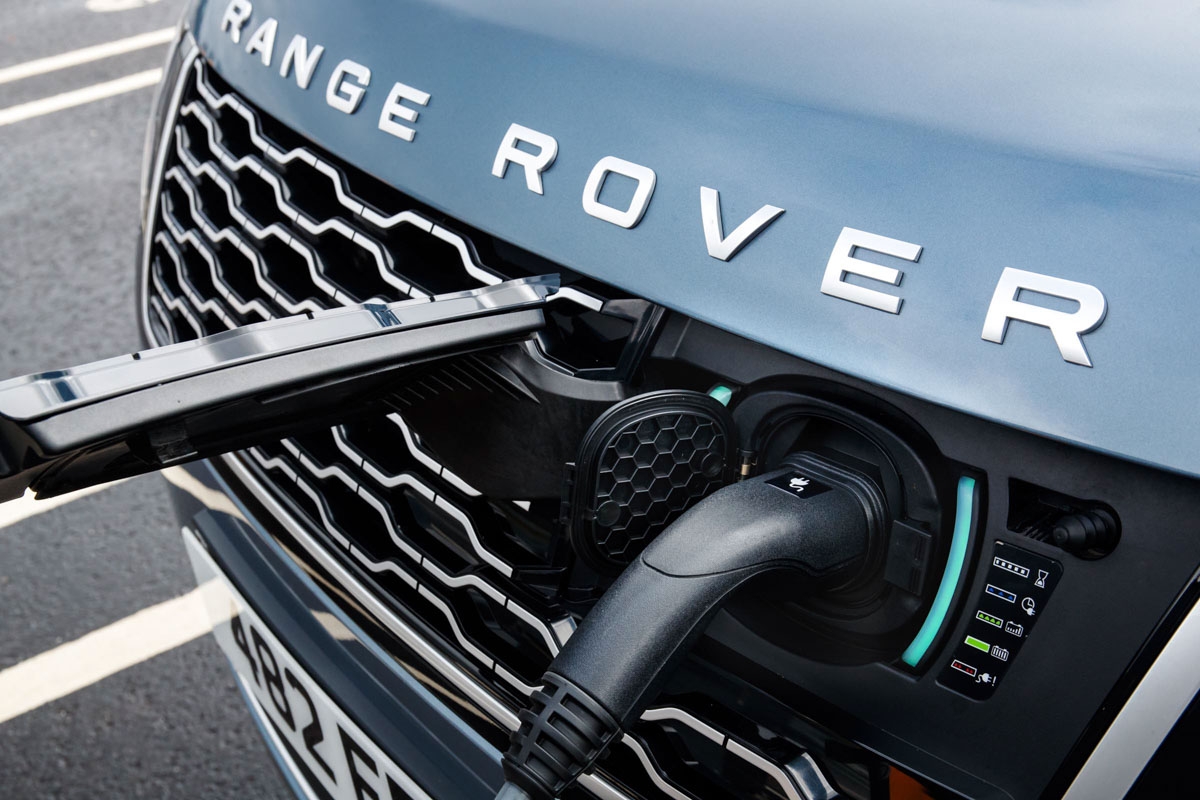

Power is sent to all four wheels through an eight-speed automatic transmission, allowing for a 0-100kph run of 6.4sec (6.8sec to 100kph) and a 220kph top speed – figures that just eclipse the V8 diesel. At the other end of the scale, Land Rover quotes up to 50 kilometres of all-electric running, at up to 137kph. A more realistic EV range is around 32kilometres, requiring a 7.5-hour charge at 10 amps (think a regular three-pin plug) or a 2h 45m top-up at 32 amps.

Technical highlights

Land Rover’s hybrid features work much like many other makers’ setups, but the novelty here is that the company has been able to combine it with all the other electronic toys you’d usually expect on a Range Rover.

You can, if you so choose, drive the car off-road entirely in EV mode, since the electric motor acts through the four-wheel drive transmission, and Land Rover’s familiar Terrain Response functions all operate quite happily in EV mode too, regardless of the surface you’re traversing. Indeed, it’ll wade (at up to 900mm) in EV mode, but Land Rover recommends the engine be running to prevent water entering the exhaust system.

Elsewhere, the Range Rover benefits from a host of upgrades across the range. Visually there’s a new grille and various LED headlight options, while the front and rear seats have been redesigned, with a minimum of 16-way electric adjustment and up to 24-way adjustment in range-topping models.

A notable addition is the two 10-inch touchscreen setup first seen in the Velar, allowing dominion over everything from navigation and entertainment to adjustments of the Terrain Response system. It looks great and operates well at a standstill, but experience with Audi’s similar two-screen system shows there’s room for improvement at JLR – the Touch Pro Duo setup can be slow to respond, and lacks haptic feedback.

What’s it like to drive?

Our main concern, and probably a concern for owners, will be whether the plug-in Range Rover delivers the levels of performance and refinement we’ve come to expect from the V6 and V8-engined models.

In short, it does – but only up to a point. The good news is that the car is predictably silent when running in EV mode – enough so that, as is often the case, it’s always slightly disappointing when the combustion engine engages – and the combined efforts of electric and petrol power deliver performance that’s suitably on-par with the other engine options.

The electric motor’s low-end effort seems to be key to that, giving the Range Rover P400e smart acceleration with relatively little accelerator input, and even when the petrol engine joins in, it remains quiet enough so as to be largely unobtrusive.

The exception to this is when you’re really working the drivetrain hard, at which point the Ingenium’s downmarket four-cylinder blare becomes all too apparent. Thankfully, the acceleration at this stage is brisk enough that you’ll only have to suffer it for a matter of seconds, but it’s not the cultured tone you’d get from any other Range Rover power unit.

Our only other demerits are related to some of the system’s quirks. Like many hybrids, brake pedal feel is below par. Range Rovers tend to have a soft pedal anyway, but the occasional regenerative effect adds an element of inconsistency. Likewise, the accelerator pedal’s response varies depending on which combination of power the car is using. Sometimes you’ll get a smart step-off with the electric motor, other times a pause and surge when the engine alone seems to be doing the work.

At 2.5 tons – within a few kilos of the V8 diesel and about 250kg more than the V6 petrol or diesel – the P400e behaves much like its brethren on the road. It is not a car that feels natural being “hustled” and is also not a car with responses that encourage such behaviour or deliver much joy in return when you do indulge. The lightweight and languid steering and the aforementioned elastic response to the brakes and throttle see to that.

Yet there remains something very satisfying about piloting the full-size Range Rover, which seats you high enough to see over hedges and avoid spray or headlight glare, surges like a powerboat when you squeeze the right-hand pedal, and rides just smoothly enough to allay concerns about puddles, potholes or other tedious road hazards.

Price and rivals

Range Rover’s P400e plug-in hybrid is priced at $230 more than the equivalent 4.4-litre SDV8. In Vogue trim that comes in at $121,735, in Vogue SE it’s $130,835, and you’ll pay $148,195 for an Autobiography.

That each powertrain option performs similarly means some may feasibly cross-shop the pair. Your choice will come down to two things, we suspect – driving experience, and running costs. The SDV8 is the more pleasant power unit to use on the move and delivers the nicer engine note when accelerating briskly, while the PHEV allows for near-silent running and, in EV mode, a mite less vibration. On a long cruise, we also suspect the SDV8 might just have the edge in economy terms – its “extra urban” figure of 7.6L/100km certainly looks better than the 30-ish we saw in mixed driving in the P400e, and diesel does tend to be the better option for a constant cruise.

Conversely, a full charge on the P400e’s batteries should see you use very little fuel at all if your most frequent trips are short, and while the 2.8L/100km combined figure is closer to fantasy than it is reality, the corresponding 64g/km CO2 rating means a $21 first-year VED bill rather than $1680, and a 13 per cent BIK rate rather than 40 per cent.

This article originally appeared at evo.co.uk

Copyright © evo UK, Dennis Publishing