Automated gearboxes have their place, but nothing can beat a great manual shift for ultimate car and driver interaction

Is ‘snickety’ the most desirable adjective? ‘Slick’ and ‘positive’ are oft-used, but I think ‘snickety’ is reserved for special occasions. Is ‘sloppy’ less desirable than ‘agricultural’ or ‘obstructive’? If I said ‘knuckly’, which manufacturer would you think of? ‘Click-clack’ used to instantly summon images of Ferraris until Audi realised there was no copyright.

The manual gearbox has a very definite language. You can still select a gear with a paddle, but you can’t ‘slot’ second or ‘punch’ into third. The exploratory waggle to check for neutral is only available with a stick. Resorting to first while moving is always worthy of mention. ‘Heel-and-toe’, ‘power shift’, ‘dog-leg’… all things that are banished from write-ups on two-pedal cars.

Why mention this? Well, I think it shows just how much a manual shift brings to the driving experience in a car. I don’t want this to be seen as an article that is negative towards paddles. A world without the theatre of a Ferrari 812 Superfast’s rapid-fire downshifts would be a much poorer place. And if you’re trying to set a lap time then there is no question that PDK, DCT, DSG and their ilk allow you to shave crucial tenths and will help get most of us closer to mimicking the sort of metronomic precision that is desirable lap after lap. They’re easier in traffic too.

But as good as paddleshifts are, manuals still matter. They are the vinyl to music’s Spotify. The log fire to the electric radiator. The mechanical instead of the quartz watch. The magazine feature to the online article. It’s about more than the end result of a changed gear, music heard, heat produced, time told or information imparted.

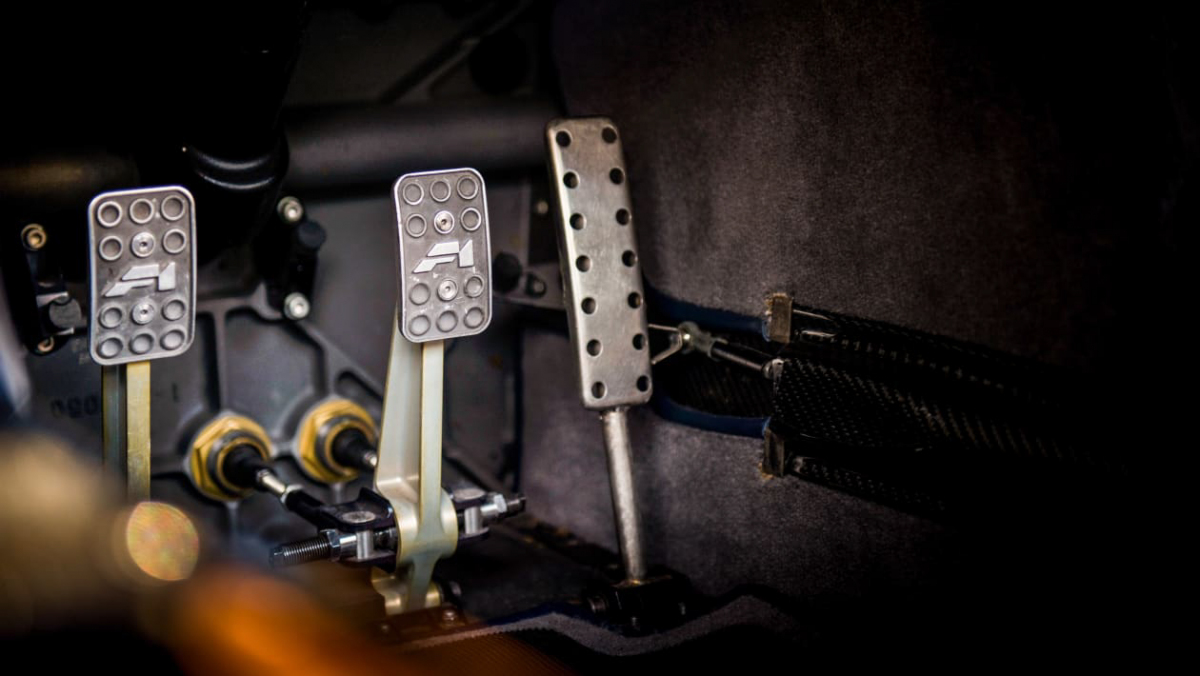

When you ponder what the simple pull of a paddle is replacing, it’s quite astounding. The actual movement of a gearstick from one gear to another is only a small part of the feel and dance of a shift. For a start, there is the way that you dip the clutch. Is that left-hand pedal hefty enough to require gym visits or so light that you stamp the carpet first time out? Does the clutch have a high or low biting point? Engagement like a light switch or worryingly slurry? And how much pedal travel do you have to play with?

Then there is the throttle pedal that requires lifting and reapplying (or perhaps doesn’t if you’re a road tester trying to shave another tenth from a 0-100kph run). Right foot timed, of course, with the action of left foot, while speed and aggression are appropriately matched with the swiftness of the lever across the gate. Different shifts will require different lengths of time and consequently this might have an impact on your decision to even make them. Last gasp into a corner while braking hard you might think that slamming forward from fourth to third in a six-speed ’box is possible, whereas pulling back and across from third to second with the need to change vertical plane is not.

The specific car and ’box will have a bearing on this too – some shifts can be flashed through, some need patience and care. Adjusting to each individual shift pattern and the associated springing is always interesting. Third to fourth is arguably marginally easier or slicker in a six-speed layout than in a four-speed, because the lever is naturally centred. And it’s the addition of an extra plane further away from the centre point that can make seven-speed ’boxes tricky.

Each shift in each ’box has a movement and pressure pattern all its own. Something that certainly can’t be said for paddles. My favourite shifts are generally a second to third or fourth to third in a six-speed box. Third to second is generally more enjoyable in a left-hand-drive car as the lever is being pulled towards you rather than pushed away. Sometimes there’s the more fundamental question of how many gears there are at your disposal. That moment not long after picking up a hire car when you are flat out in fifth and wondering if a pull back will find sixth or reverse…

Talking of being flat out in fifth, the manual gearbox can certainly heighten your awareness of speed. I’ve been lucky enough to experience both a 991 GT3 RS and 991 911 R at high speed on the autobahn. Differing aerodynamics aside, it feels like a considerably more considered moment when you take one hand off the wheel to change from fifth to sixth at over 8000rpm and 257kph than when you extend a finger to flick a paddle.

Of course, a good manual gearbox is also a delight when you’re not going quickly. A simple blip to match the revs on a downchange, or a slow but perfectly smooth upchange are things that can be enjoyed at any speed and leave you feeling more connected to the engine. However, the low-speed heel-and-toe must be one of the trickiest actions to perform in a car and I think it’s why it can be off-putting to learn. It’s much easier when you are leaning hard on the brake pedal and have a relatively firm platform from which to articulate your foot across to the throttle pedal.

At slow speed a knob can also remain a delight to fondle (please do stop sniggering at the back). Many different shapes and sizes (seriously now, just pack it in) have been tried over the years, but the simple sphere is still the benchmark in many people’s palms. Part of the reason must be that no matter what the direction of the lever’s travel or how it is held, the ergonomics of the knob are identical.

Now, this article wouldn’t be complete without a few specifics. Some case studies. A little idle contemplation of the best manual shifts evo has experienced. My personal highlights begin with the short, tight throw of a Honda S2000. The Japanese brand has had many excellent shifts, but this always sticks out for me. Snickability through and through. Sticking with Honda, the latest Ariel Atom has a tremendously quick, precise shift. In fact, for pure speed around the gate it is probably only bettered by Prodrive’s masterpiece of a H-pattern dog ’box in its Impreza rally cars. The N2009 iteration was just sensational in the way it could be flicked around a gate that felt no bigger than a small box of matches. It was as though the lever knew as soon as you put pressure on it where you were trying to send it and then flew across to the next ratio.

The six-speed from a 997 911 and various Boxsters has been praised on numerous occasions and is an absolute cracker. It has the most wonderfully smooth and perfectly spaced throw. It’s just a shame it’s a little tall in the actual gearing. The Boxster’s bigger mid-engined cousin, the Carrera GT, often gets cited as having one of the best shifts, and while it is perfectly placed – easily to hand, high up near the wheel – I think it is arguably a little light in its action. However, what is brilliant is that this lightness, while not as tactile as even in the aforementioned Boxster, suits the drivetrain it is attached to perfectly. The lack of inertia in the way the V10 revs requires a shift that is almost ethereally light and the birch-topped lever delivers.

To that extent an old Land Rover with revs that rise and fall in time with the passing of the seasons also has the perfect gearbox, in the sense that it requires long pauses and much patience to snag a clean shift. The long pudding stirrer of a gearlever which has the vagueness of a late-night cocktail recipe is perfectly befitting of the machine it’s in and the mien of the journeys you expect to undertake.

Anyway, back to some more conventional praise. A V8 Audi R8’s gearchange is wonderful for the sense that you are drawing a sword from a scabbard and then sliding it into another. The diamond-knurled lever is pleasing too and the weighting is satisfying, although it isn’t a shift to rush across the gate. Price needn’t inhibit an enjoyable gearbox either, as the Ford SportKa showed. The five-speed in the early R50 Mini Cooper is a peach too, and a Mk1 MX-5 provides a lovely shift for not a lot of money.

My top two gearshifts, however, are both in Ferraris. The first is the F50’s. Like the Boxster, it gets the weighting of both pedal and shift absolutely right, while the sphere on top of the lever is classically perfect in the way it sits in the palm. There is the added thrill of the open gate too, but with a touch more creaminess than in the R8. It is just sublime.

The other Ferrari is emblazoned on my mind really on the basis of a single shift. A 250 Testa Rossa is all about the drivetrain, and the gearshift has the mechanical tactility of turning a big, well oiled key in an old church door. Why one particular shift? Well, you need to double de-clutch for most of them, but from first straight back to second is just a dip of the clutch and brief lift of the centre throttle(!) as you pull firmly back on the tall, straight lever. It’s a short action and an abrupt stop, like a sequential shift but without the return. The fact that it is changing the pitch of the most fabulous 3-litre V12 soundtrack certainly helps it stick in the mind, but the positivity and sense of connection to the meshing cogs is unrivalled in my experience.

Of course, all this praise is in danger of becoming a wistful reminiscence before too long, because the manual is rather an endangered species amongst new cars. However, the fact that Aston Martin still sees fit to produce a manual for the Vantage, the fact that the biggest criticism of the brilliant Alpine A110 is the lack of an H-pattern, and the fact that Porsche decided to reintroduce a manual option to the GT3, surely shows that the importance of three pedals is still felt strongly. May that feeling last as long as it takes to get second gear in a cold Ferrari 348.

This article originally appeared at evo.co.uk

Copyright © evo UK, Autovia Publishing