By 2016, BMW’s Spartanburg plant will be the company’s largest anywhere in the world, churning out almost half a million cars a year. But despite the German sounding name, Spartanburg isn’t in BMW’s homeland of Bavaria. It’s in South Carolina, USA.

So how did one of Germany’s finest brands come to build its most productive facility in the US state historically noted for its acts of rebellion? South Carolina was the first state to declare independence from the British ahead of the American Revolution, and the first to secede from the Union, prompting both the American War of Independence and then the American Civil War. The towns of Greenville and Spartanburg sit to the north of this green and mountainous state, and until the early ‘90s the population worked in the fading textile industry.

Then in 1992, BMW decided it should strengthen its international assembly facilities, as the E36 3 Series was proving a global hit. It chose for this new plant a patch of land close to the main road connecting Greenville and Spartanburg, just outside the small town of Greer.

Two years later, the Spartanburg plant went online and started churning out the lowly 318i for both American and international markets. A year after that, it started making the Z3 roadster as well. All was bimbling away nicely as Spartanburg meekly took its place among the increasing number of assembly plants BMW was building around the world.

But then in 1999, BMW decided that the world needed SUVs. It created the X5 and chose Spartanburg to build this new vehicle. No one really knew how well it would do. In case you’ve been living in a cave since 1999, here’s how well it did: VERY. The X5 was a smash hit around the world, and the kick-starter for an ever-increasing number of X model SUVs, the latest of which is the second-generation X6.

And demand for the X models is still growing. Today, there are five X models – the X1, X3, X4, X5 and the X6 (which crankandpiston.com test drove recently), and they make up 28 percent of all BMW’s vehicle sales globally. Of those, the X3, 4, 5, and 6 are built in Spartanburg. In the Middle East, the popularity of the X models is even higher – almost half of all BMWs sold in the region fall into that range. The old X6 on its own made up 15 of total sales in the region.

A new model – the X2 – will join the line up next year; a smaller coupe-like SUV very much inspired by the X6. A larger X7 is also planned, which will also be built at Spartanburg. But the problem is that demand for the X models is exceeding supply – BMW literally cannot build them fast enough, and so it’s ploughing a massive $1 billion into the Spartanburg plant over the next two years, expanding product capacity by 50 percent. The plant already churns out more than 1000 cars every day – by the time the upgrades have completed in 2016, the plant will be producing 450,000 vehicles every year, some 70 percent of which will be exported to 137 different countries. That means it’ll overtake BMWs current biggest producer, Dingolfing in Germany.

A walk around the 1150-acre Spartanburg site is eye-opening (and done so without a camera, hence the press images you see above and below), because the scale is so immense. It boasts some 5.6-million square metres of under-roof space, and in Hall 52, where the X5 and X6 are produced, the paint shop stands seven storeys high. There are two assembly halls, three separate body shops and a café that’ll seat more than 1000 of Spartanburg’s 8000 employees – or ‘associates’ as BMW prefers to call them – at a time. There’s even a pharmacy, and a medical centre. Out the back, a railway line runs directly into the plant so that the finished cars can be loaded onto trains and taken directly to the port of Charleston.

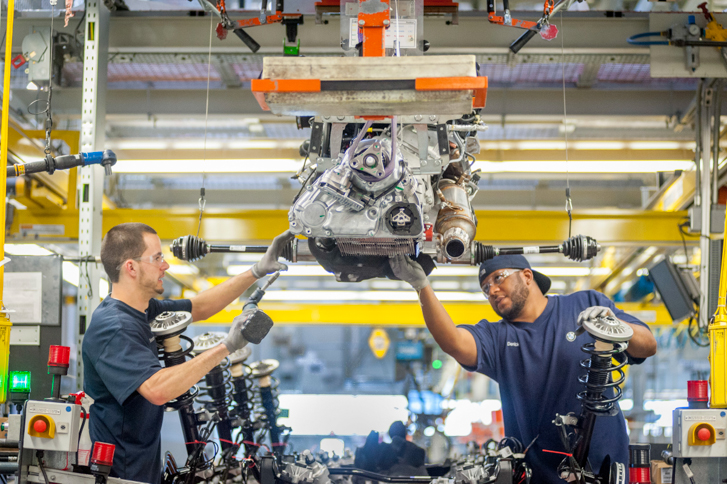

The interior of Hall 52 is a sight to behold and an indication of how far manufacturing has come in the history of the automobile. BMW is not alone in having a highly regulated and large-scale plant, but that doesn’t stop a slight feeling of awe at how well the individual elements of such a massive operation fit into each other like clockwork. The organisation is precise and defined, with each worker on the huge production line aware of exactly what they need to do and how long they have to do it. The line moves continuously – one vehicle is finished every 100 seconds, with automatic, driverless carts scooting between rows, delivering stock to each station. No stock is allowed to sit in the plant for more than two-and-a-half hours, which means precise planning to manage delivery of parts from 170 suppliers across North America.

With so many vehicles being produced so quickly, ensuring that quality remains high is a huge priority – these aren’t econoboxes, these are BMWs. Consequently five cars are pulled off the line each day for thorough inspections, and a team of roaming inspectors prowl the lines, performing spot checks during each shift. Any issues are flagged up to the section managers to brief their teams, who work 10-hour shifts, two shifts a day, six days a week.

Notably absent are robots, normally a common sight in assembly plants of large volume manufacturers. Not here, explains assembly manager Chris Kirby, who points out that customers expect a certain level of quality from a brand like BMW. That’s not just about fine tolerances, it means adding a personal touch by making the cars by hand wherever possible. “Our associates are craftsmen, and to build our cars they have to understand, with the complexity we have, exactly what’s expected of them,” Kirby says. “We pride ourselves on having less automation.”

In just 20 years, the Spartanburg plant has grown from nothing to become the jewel in the crown of BMW’s new SUV horizon. With demand for X vehicles showing no sign of abating, it’s perfectly placed to provide.

“The X7 is pretty much based on the X5, which is already built here,” says Chris Kirby as he surveys his workforce. “The US market is one of the top three markets for BMW Group and so it makes perfect sense that the expansion would take place here.”

In the time it’s taken you to read this article, at least five BMWs have rolled off the Spartanburg line. The next time we write about the plant, it will be even more than that.

– Our thanks to BMW Middle East