Can high-performance fun and a plug really coexist in one car?

It seems like no time at all since performance hybrids were restricted to the realm of the seven-figure hypercar, but in 2021 the hybrid performance car is no longer quite such a misnomer.

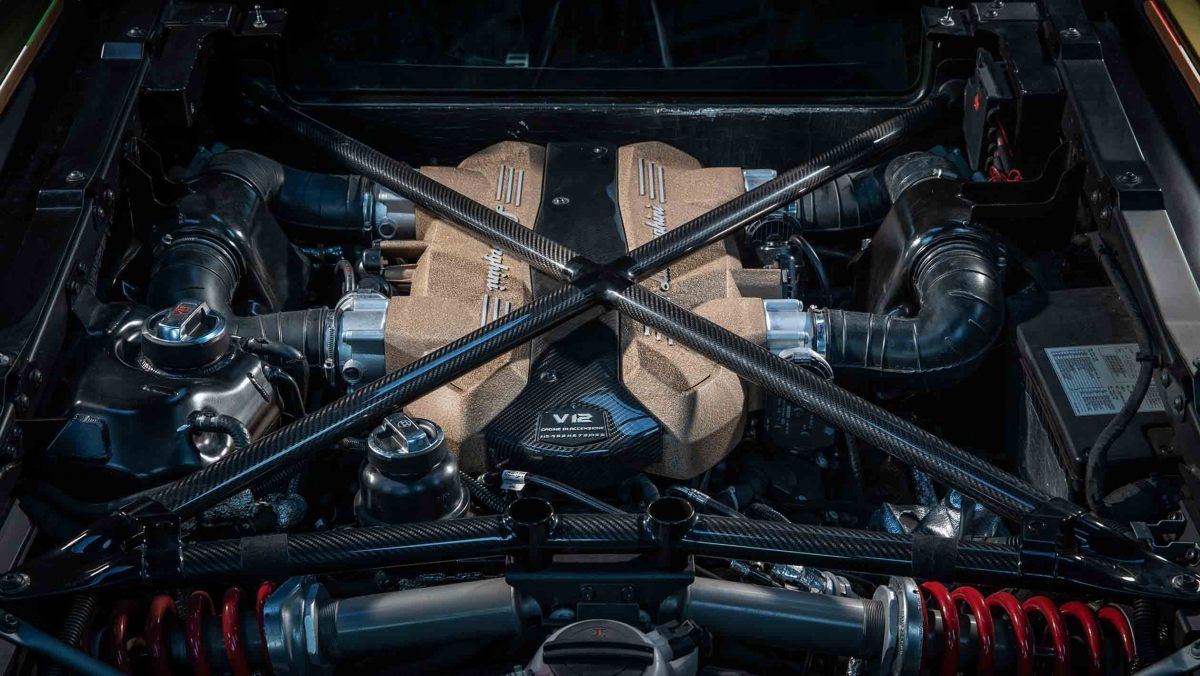

From hot hatchbacks and performance saloons to sports coupes and supercars, electrification is spreading across the market faster than ever, and due to ever tightening legislation around fleet-wide carbon emissions targets, is becoming a way to ensure manufacturers aren’t financially penalised for producing these sorts of high-performance, high-profit models.

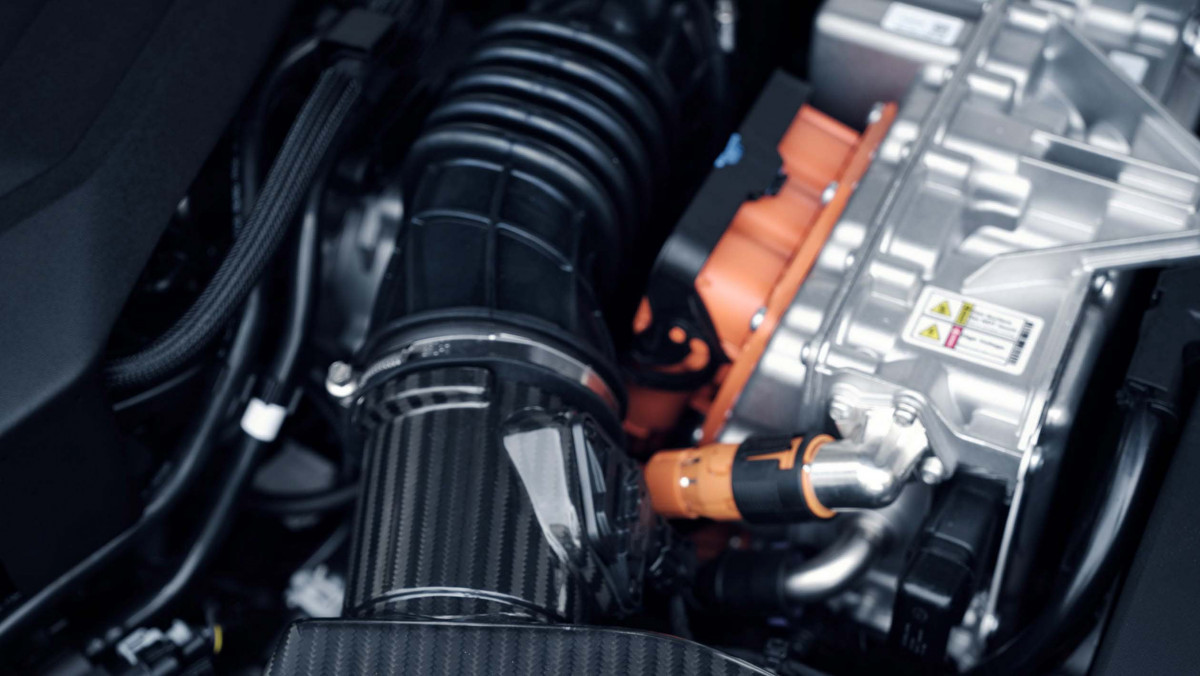

Aside from the legislative benefits, when applied to performance cars electrification does have other traits, both positive and negative. It can be used to supplement a combustion engine – flattening torque curves, providing an extra kick when moving off the line and spinning up large turbochargers before the exhaust gases have reached it.

The caveats, however, include excess weight. Batteries, motors and all the associated hybrid car gubbins are heavy. The hybrid VW Golf GTE weighs a full 170kg more than its petrol GTI cousin, and that additional heft blunts performance and handling. Then there’s the issue of response – with two propulsion systems and two braking systems, the complex calibration between a hybrid car’s powertrain components is proving to be more problematic the more we drive them.

So while there’s still a lot of work to be done in making these cars as entertaining as those with no hybrid assistance, we’ve cherry-picked the best hybrid performance cars on the market today, while also looking forward to a few manufacturers that are on the cusp of their own hybrid revolutions.

Hybrid car technology explained

Before we get into listing our favourite hybrid cars of today, some explanation. The term ‘hybrid’ is a relatively loose one as there are a few different ways of adding electrical assistance to a car with an internal combustion engine. We’ve rounded the key hybrid car technologies below…

Mild Hybrid – MHEV

The mild-hybrid car has perhaps seen the most growth over the last few years, with almost all manufacturers incorporating some form of subtle electrification into their existing engines as a short-term way of reducing CO2 emissions. There is no singular form of mild-hybrid system, with different manufacturers using the technology in different ways, but for simplification’s sake, mild-hybrid powertrains are generally unable to drive the car on purely electrical power, and usually include a very small lithium-ion battery.

The most common and now widespread mild-hybrid system is the relatively simple Integrated Starter Generator (ISG) or Belt Driven Generator (BSG) fitted to take some of the strain away from the engine itself. This can be as simple as the ISG taking the place of a traditional starter motor, which can also simplify the front of the engine with ancillaries such as water pumps, fuel pumps or air conditioning condensers being driven electrically, rather than from the crank via belts.

The next step is the application of a more powerful 48V electric circuit to power elements that would otherwise be too powerful for the usual 12V system to sustain. These systems are generally found on larger cars such as SUVs and GTs, with the VW Group making wide use of a 48V mild-hybrid system to power active anti-roll bars or electrically driven compressors that prime turbochargers to reduce lag.

Some mild-hybrid systems feature enough of an electrical kick to augment the engine’s performance directly, as seen in some Mercedes-AMG models such as the CLS53. In this case, the ISG provides a kick of 21bhp and 146lb ft of torque that blend into the power delivery to torque-fill at low rpm. At the extreme, this is also the system used in modern Formula 1 cars as KERS.

Parallel hybrid – Hybrid or ‘self charging’

The parallel-hybrid system was pioneered by Toyota and was one of the first mass applications of the technology, going on to become the backbone of Toyota’s global engine range. The system is similar to a mild hybrid, but the electric motor and battery pack are large enough to momentarily drive the car independently.

Both petrol and electric power sources work either together or separately depending on what the car’s internal brain thinks is the most efficient mode, and when under hard acceleration or high speeds, both power sources work together to provide more power.

This type of hybrid is falling out of favour with many manufacturers, as the on-paper CO2 reductions are not as substantial as those of plug-in alternatives, despite real-world usage between the two – especially when access to a charge point is limited – often favouring parallels.

With less variety to the drive modes, the calibration of how each of the two powertrain elements interact can also be more finely tuned, especially as manufacturers attain more experience with this technology – this is exemplified in Toyota’s case, as four generations in the Prius is remarkably efficient, despite rarely running purely on electricity.

Plug-in hybrid – PHEV

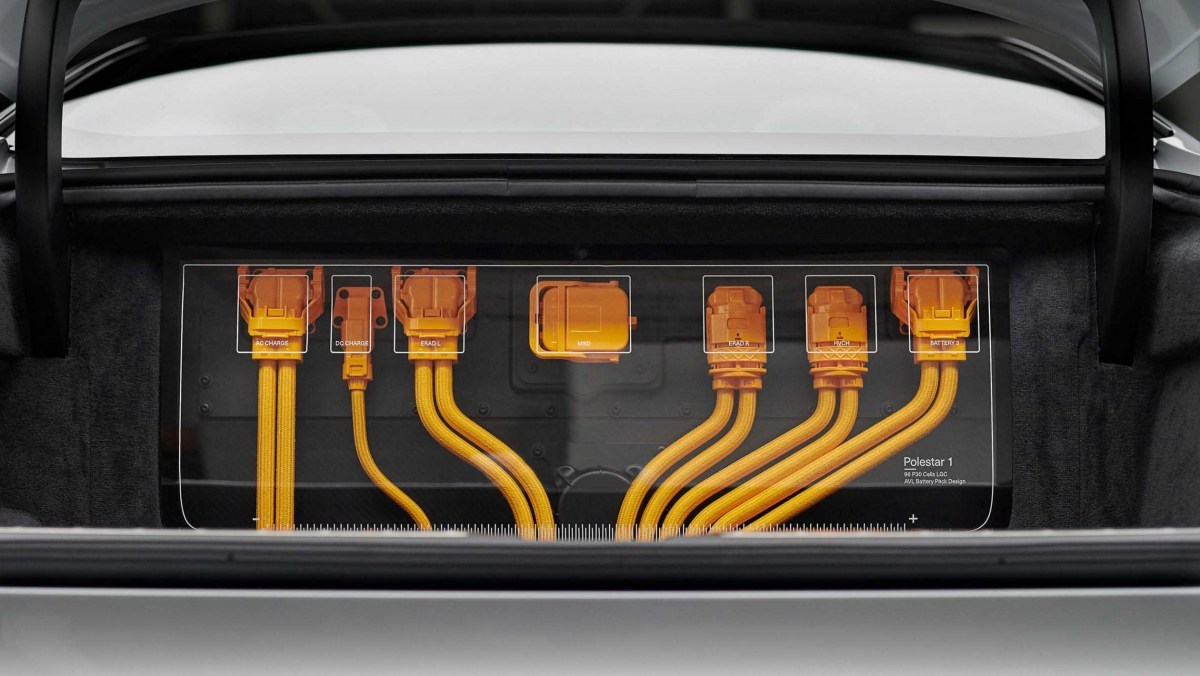

Plug-in hybrids have more of an all-you-can-eat mentality to the amount of hardware packed into their powertrains, which has its own benefits and compromises. All plug-in hybrids are designed to be able to run for an extended period of time on electric power alone, which means bigger and beefier electric motors, plus a much larger battery pack to feed them.

In some layouts, like that found in the BMW 330e, the electric motor is placed after the transmission, with the electric drive driven through the same propshaft and rear differential as standard combustion models, but not the standard transmission, reducing parasitic losses.

Some more complex systems, such as that found in the new Peugeot 508 PSE, utilise multiple electric motors as well as the combustion engine. In this case, the rear-mounted electric motor drives the rear axle independently, with both the usual transversely mounted combustion engine and a smaller electric motor powering the front.

Mercedes-AMG is poised to introduce an even more complex arrangement with its new e-Performance models, with power from the front-mounted combustion engine being sent to the rear wheels, where drive will be joined by a powerful 201bhp electric motor via its own two-speed transmission. Things get even more complicated when slip on the rear axle is detected, as power from both electric and combustion powertrains is then sent back up to the front wheels.

If this sounds complicated, it’s because it is, and that complexity comes with the cost of both excess weight and a difficult job calibrating it all to feel natural and consistent. An example could be made with the Peugeot 508 PSE, which has proven that while the chassis is superbly set up, blending two electric motors, a heavily boosted combustion engine and an eight-speed automatic transmission has given Peugeot plenty of calibration work, with lots more still to do…

Brake feel is another element that’s often unnatural in hybrids, but particularly in performance hybrids, as there’s yet more contrast in feel and response between high-powered friction braking and the regeneration capability of electric motors.

This article originally appeared at evo.co.uk

Copyright © evo UK, Dennis Publishing