Today’s turbocharged Ferraris deliver a smooth hit; the 288 GTO and F40 thrilled with a much wilder ride

The infamous Group B regulations for racing and rallying, introduced by the FIA in 1982, resulted in some of the most powerful, rapid and technically advanced competition cars ever seen. Apart from the requirement to construct a minimum of 200 cars for homologation, there were few other restrictions on what the manufacturers could build. High-tech materials such as carbonfibre were permitted so weight could be kept low, and turbochargers were allowed without any limits on boost. The engineers naturally embraced this new freedom, and the result was a group of exceptionally powerful cars, including the Ford RS200, Lancia 037, Peugeot 205 Turbo 16 and, of course, the mighty Porsche 959. By 1986, some of the Group B rally cars were producing upward of 500bhp and have since become the stuff of legend.

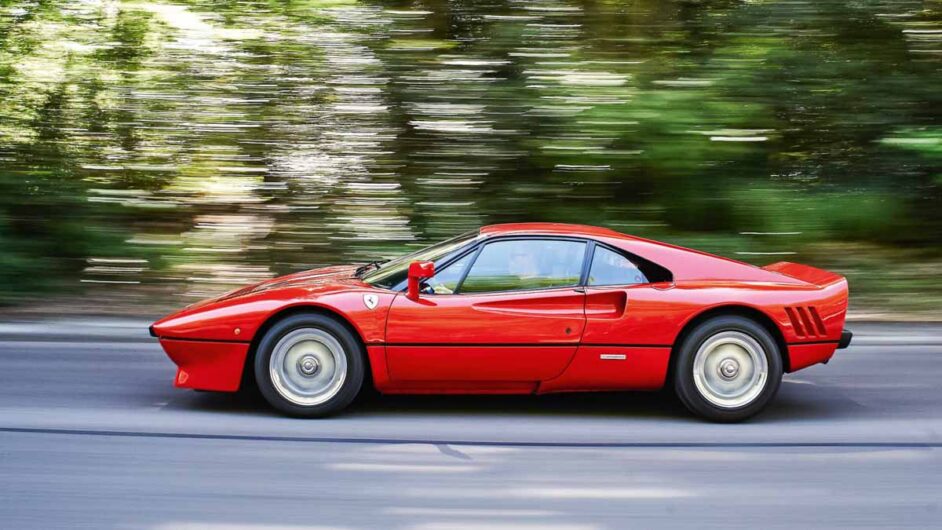

Ferrari decided to enter the fray, too, and began to develop a Group B car for the anticipated race series and possibly also for tarmac-based rallies. The 288 GTO was launched in 1984, using a twin-turbo 2.8-litre derivative of the V8 engine from the 308/328 (2.8 litres to give an FIA turbo equivalency rating of just under 4 litres). Its architect was Ferrari’s F1 designer, Dr Harvey Postlethwaite, and it was everything you’d want from a Ferrari bearing the GTO name: fast, beautiful and charismatic.

> Porsche 959 – review, history, prices and specs

Unfortunately, the anticipated race series never took off; privateer teams preferred to go sportscar racing with less expensive alternatives, and then in 1986 came the deaths of Henri Toivonen and Sergio Cresto on the Tour de Corse and the FIA pulled the plug on Group B altogether. As a result the 288 GTO never fulfilled its raison d’être. But what it did do was demonstrate Ferrari’s grasp of the latest technologies – and in the process its engineers created one of the greatest roadgoing supercars of the era. In a three-year production run, some 272 were built, and today they’re among the most coveted of all Ferraris.

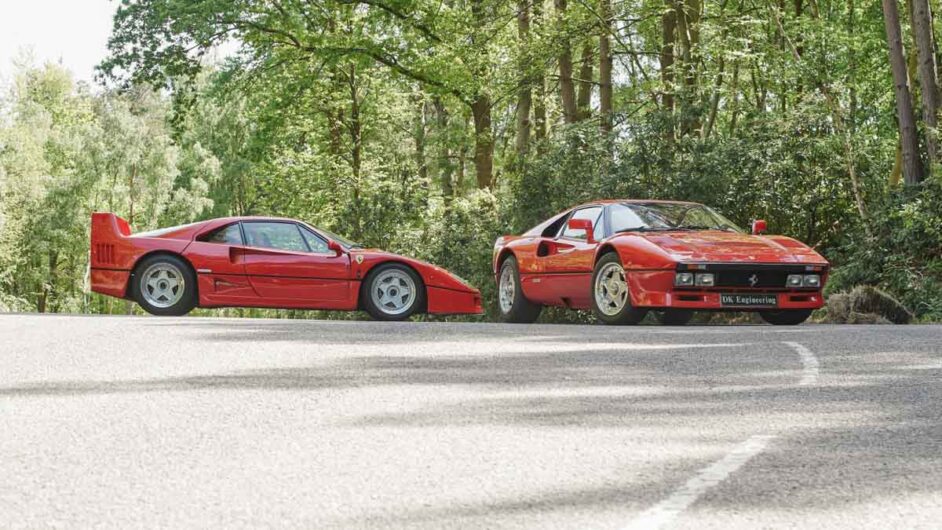

By comparison, the F40 that replaced it in 1987 is almost commonplace, with more than 1300 having been built in its own five-year production run. Not so rare, then, but even faster and every bit as desirable. This promises to be a day to remember.

Apparently, when Motor magazine went to pick up one of the first 288 GTOs from the factory, they were somewhat taken aback. They’d been expecting something closely related to a 308, only better. Of course, anything built to take on the monsters of Group B had to be a greater leap forward than that.

Clearly there were visual similarities between the 308 and the 288 GTO, but, apart from the roof and glass area, little else was carried over. The GTO had a much wider body to encompass a wider track and broader tyres, and a longer wheelbase because the V8 had been turned from transverse to longitudinal to accommodate twin IHI turbos, intercoolers and new Weber-Marelli fuel injection. To keep weight down, the body featured Kevlar and carbonfibre and was mounted on a tubular chassis as opposed to the 308’s semi-monocoque. The net result was that, at 1161kg, the 288 was some 110kg lighter than the 308. And with power up from 240 to 400bhp, performance was from another dimension.

As I approach the 288, it looks threatening, as if it’s about to bite me, while its swollen rear haunches with their slashed vents are reminiscent of that earlier icon, the magnificent 250 GTO. Time to climb inside. According to DK Engineering’s Harvey Stanley, the seats in a 288 were available in two sizes, small or large. These are rather tight so I figure they must be the small size. As standard they were finished in red fabric, but customers could pay extra for full leather, and also for air-conditioning and electric windows. This car has the lot. So here I am in a full luxury-spec no-expense-spared 288 GTO.

In front of me is a speedo reading to 320kph and a tachometer reading to 10,000rpm, with a red sector starting at 7800. Between them are smaller gauges for turbo boost and oil pressure, while across in the centre console are three more: fuel and water and oil temperature. The 2855cc V8 fires up instantly, and I watch the instruments carefully as I patiently wait for things mechanical to come up to temperature. Originally the 288 GTO would have had the usual four-tailpipe exhaust system, two either side. This car, as with many other 288s, was modified, either at the factory or later, with an Ansa two-pipe megaphone system and it sounds amazing. Even on tick-over it is raucous and dramatic.

> Ferrari F50 – review, history, prices and specs

Select first – towards me and back on a dog-leg – then away. To start with, I keep it nice and gentle. The unassisted steering lightens up once you’re on the move and, trickling along at around 3500rpm, the 225/50 ZR16 front and 255/50 ZR16 rear boots feel firmly planted. It’s a hot day but the air-con works well and the cockpit is comfortable. For such a threatening-looking machine, I am beginning to wonder what all the fuss is about.

After a few laps of the track, I take the plunge and floor it in second. As if by some demonic spell, Dr Jekyll changes to Mr Hyde as the rear wheels spin and the back end squats. As the turbos blow, the coarse exhaust note changes to a metallic scream and the tachometer needle flies. At 7000rpm, as my back is being pushed hard against the seat, I pull the long gearlever back into third and floor it again. The acceleration is mighty. I guide the lever into fourth via three conscious movements: forward, across – clack – and forward. Sounds slow, but trust me it’s not. Care and precision through that exposed gate result in the sweetest, most rewarding gearchange imaginable.

The 288’s brakes are excellent, with good feel and reassuring bite. Whereas at low speeds the chassis feels rather stiffly sprung, at speed the suspension has a fine blend of suppleness and control. I’m really warming to it, and I have to remind myself that this car is worth in the region of $2.6 million and I’ve promised DKE’s David Cottingham and Harvey Stanley to treat it accordingly. Thus, at the speeds I’m driving the 288 today, it behaves impeccably. But I know only too well that it can be a colossal handful on the limit and an absolute devil to get back when it gets away from you. The unenlightened have been known to enter a bend in a 288 GTO with the engine off-turbo and then naively plant the throttle mid- corner. A driver in control they cease to be and a passenger most terrified they rapidly become, an indignity I have so far managed to avoid.

It’s sad that this mighty Ferrari was unable to prove itself in the heat of Group B competition. But as a roadgoing supercar – and a showcase for early-80s tech – it was up there with the best of its era.

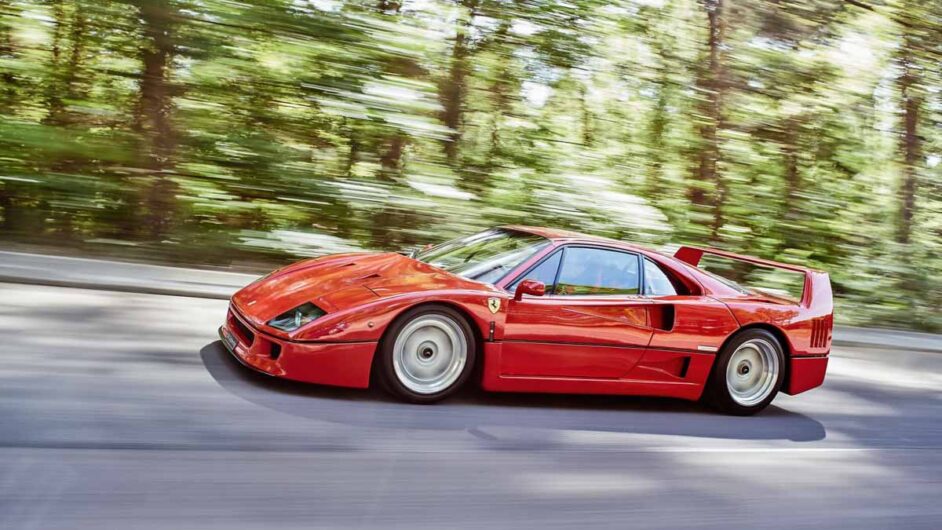

The F40 may not be as elegant as the GTO but, with its ground-hugging stance, high-rise rear wing and its nose and flanks peppered with NACA ducts, it is considerably more dramatic and undeniably purposeful. I peer through the slotted Perspex engine cover at the 2.9-litre twin-turbo V8 and admire a view that, even after all these years, still causes my heart to miss a beat.

It’s ten years since I last sat behind the wheel of an F40, but as I am climb over the high carbonfibre sill and lower my rump into the seat, it feels like I’m home again. The carbonfibre-shelled buckets, finished in red cloth, could be ordered in small, medium or large, though Pavarotti had Testarossa-style seats fitted as he was too big for any F40 seat. But then he never drove his F40 anyway.

You can’t help but be impressed by a speedo that reads up to 360kph. To its right is the tachometer, calibrated to 10k, and to its left the water temperature gauge and another dial, reading from 0-1.5 bar, for the turbo pressure. Oil temp, oil pressure and fuel are covered by three small dials in the centre of the dash. I strap myself into the full race harness. The cockpit rear-view mirror is not much use but the side mirrors do offer some rearward vision. Black felt trim covers the dash, carbonfibre covers the door panels, there’s a pull-cord to operate the door mechanism and a button marked Fire to activate the plumbed-in extinguisher system. The F40 looks and feels every inch the no-nonsense, no-compromise racing car.

In fact, unlike the 288, the F40 wasn’t conceived to go racing, though it was developed from a racing car (and privateers would later campaign track versions in various GT series with no little success). The missing link between 288 and F40 was the 288 GTO Evoluzione, developed by Ferrari when it was still harbouring dreams of glory in Group B competition.

Just five (or possibly six) examples of the Evoluzione were created, and these were all pure racing cars. At 940kg, the Evo was an astonishing 380kg lighter than the regular 288 and produced 650bhp as opposed to the 400bhp of the standard car, giving it a top speed of 354kph-plus, depending on gearing. The much-modified bodywork included a deeper front air dam and a massive rear wing – almost as though the F40 was bursting out from within the prettier 288 GTO shape – and it had bigger brakes and wider wheels. It was a full-on racer. Sadly the end of Group B rendered the Evoluzione obsolete overnight.

However, when the programme was canned, Ferrari decided to use the Evo as a basis for a no-frills road car, one that would give Porsche with its tech-fest 959 a bloody nose.

Whereas the 288 GTO clearly bore a resemblance to the 308 road car, when the F40 appeared in 1987 it looked like no other roadgoing Ferrari. In fact, underneath the F40’s carbon interior and tub lurked pretty much the same steel spaceframe chassis as in the 288. Topside, though, whereas the 288 pioneered some composite panels, the F40 was all carbonfibre, and very slippery with it.

People still argue about whether the F40 ever quite achieved its claimed 323kph top speed – in every independent test except the one conducted by Italian mag Quattroruote it failed to top 320kph – but everyone seems to accept that the F40 was the fastest road car of its day, just pipping Porsche’s 959. For Ferrari it was mission accomplished.

Time to drive. Turn the ignition key fully round and then press the button set below and slightly to the left. The V8 fires with a wonderful rasp, sending a busy thrum through the cockpit as it idles. The clutch is heavy but not as heavy as I remembered and easy to modulate. The long, spindly chrome gearlever moves sweetly, if not quickly, across the gate. Select dog-leg first, engage the clutch and pull away. I forgot to bring my driving boots and have to exercise great care to avoid the welt of my right shoe catching the brake pedal as I press the throttle.

The F40 is a wide car, significantly wider than the GTO, though personally this has never bothered me. As with the GTO, but more so, the unassisted rack-and-pinion steering is rather heavy until you’re under way. But then, with chunky, 245-section front tyres, that’s hardly surprising.

After a couple of laps reacquainting myself, I hit the throttle in third and revel in the exhilaration as the engine note changes from a gentle roar to a bellowing howl and once again I am rammed back in the seat. I ease off and short-shift as a tight left-hander approaches, then heel-and-toe down through the gearbox, enjoying the way the pedals seem to be placed just perfectly for such footwork.

What I particularly like about the F40 is that it has more of a raw feel to it, and the way you seem to be more part of it than you do with a 288. In many ways the 288 is the more useable – not least because it’s that much narrower and ground clearance isn’t such an issue. It’s also less ‘obvious’. But if the road is damp, and you get a 288 out of shape, you need to be lucky as well as good to get it back. In the F40, even if you’re very sideways, nine times out of ten you’ll get it back. The steering is terrifically sensitive as well as direct and quick. The F40’s wider track helps, too – its wheels are that much farther apart and it has a huge amount of rubber on the ground. In my experience, it’s the more secure-feeling and the more forgiving.

Ten years is a long time, so, just for fun, I try a standing start. It’s just as I remembered; initially the F40 doesn’t actually feel that quick. But only until those twin turbos whack you in the back! Make no mistake, hitting 96kph in around four seconds while still in first gear still takes your breath away. The F40 piles on speed in much the same way as the GTO, but it hits even harder.

Today, of course, turbos are very much back in vogue, and nowhere more so than at Ferrari, where the 488 GTB and Spider, California T and GTC4 Lusso T all have turbocharged V8s. There’s no doubt that a car like the 488 is an absolute tour-de-force, its 3902cc engine the epitome of high tech. It features two parallel ball-bearing twin-scroll Honeywell turbos, their compressor wheels made from the same low-density alloy found in jet aircraft engines to reduce inertia and resist high temperatures within the turbo. Variable-vane technology and the latest computer- controlled fuelling and ignition means it’s able to combine brutal power delivery with an efficiency the engineers of the mid-80s could only have dreamed of. The bottom line is 661bhp at 8000rpm and 561lb ft of torque at 3000. The specific power output of 169bhp per litre and specific torque output of 144lb ft per litre are both records for a Ferrari. The 488 GTB is said to rocket from 0-96kph in under three seconds and tops out at 330kph. And yet, even with all that immense power and performance on tap, the car remains totally manageable. And the delivery itself is so linear, it almost disguises the fact that it’s turbocharged. Thirty years ago, turbo power delivery was very different.

Management systems that mete out the torque in the lower gears, stability and traction control systems, electronically controlled diffs – these things make modern turbocharged Ferraris astonishingly well-mannered and supremely drivable. They’re designed and engineered so that drivers can access supercar levels of performance without getting into trouble. They’re also refined, with suspension that can deliver comfort or control at the press of a button. Truth is, you could probably make progress every bit as quickly in a 488 as you could in an F40.

That said, the F40 itself produced a mighty 163bhp per litre, almost as much as the 488 kicks out today, and there was no stability or traction control in a 288 GTO or F40. It was a different world back then. You had to know what you were playing with, and if you didn’t, those cars would bite you hard.

In an F40 – or a 288 – the whole character of the car is bound up with the fact that you can never forget it’s turbocharged. And while the figures say it may not be any quicker than a modern 488, the unique feeling of exhilaration when those twin turbos kick in and pin you back in your seat is yet to be eclipsed. They still remain two of the most exciting and challenging drivers’ cars to be let loose on the public road.

This article originally appeared at evo.co.uk

Copyright © evo UK, Dennis Publishing