Porsche restorer, Singer, drafts in notable engineers and drivers to help develop new aircooled 911 modifications

Singer has unveiled the most extreme version of its highly modified and restored 911s to date at the 2018 Goodwood Festival of Speed. The Californian firm, which has gained notoriety backdating, updating and thoroughly customising aircooled Porsche 911s, has been working with UK-based firm, Williams Advanced Engineering to develop new upgrades for the new car’s engine, chassis and body. The project is known as the Dynamics and Lightweighting Study (DLS) and will form the basis of many future Singer restorations.

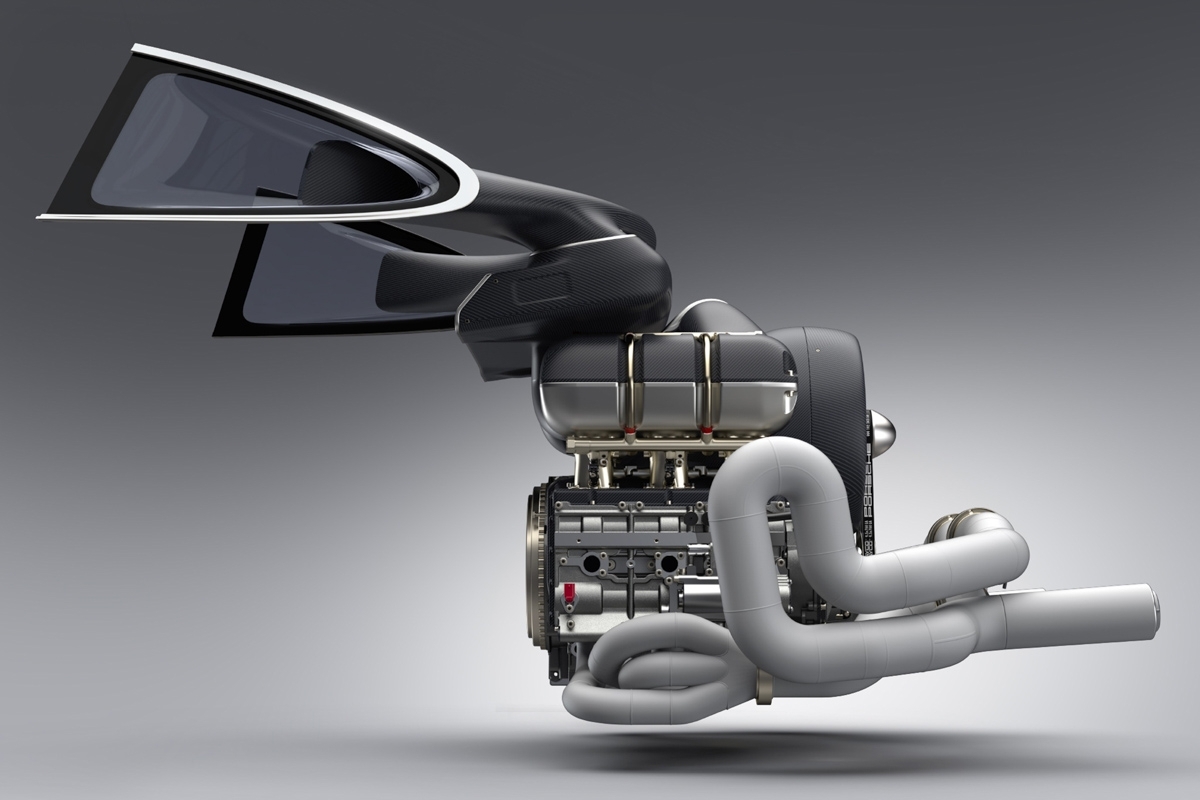

At first Singer teased us with renderings of its highly modified Porsche engine that showed a new induction system with an intake through openings in the side rear windows and a compact, yet complex, titanium exhaust system. What wasn’t visible from the images was the engine’s capacity increase to four litres, its four-valve per cylinder heads and its 9000rpm rev limit. The later we were given a taste of in a video of the engine in a test car. Hans Mezger, who designed engines for Porsche from the late fifties until the nineties, was also consulted during the development phase of the modifications.

Singer claims that its thorough engine overhaul increases the power output to 500bhp, an impressive 125bhp per litre. Performance is further improved with the significant weight loss program for the entire; the use of magnesium, titanium and carbonfibre has been used to reduce its kerb weight to 990kg.

To suit the step up in performance Singer recruited the services of Williams, again, to help tweak the chassis. Although the car is still based on a 964 – as with the other cars Singer had previously put its stamp on – the geometry and range of adjustability has been greatly improved, and many of the components are made from lightweight materials.

Racing driver, Marino Franchitti, winner of the 12 Hours of Sebring, has driven the development car: ‘Everyone is working so hard to bring that Singer magic to these restorations and what I’ve seen and experienced behind the wheel has me very excited.’

The increase in engine and braking performance, and the modifications made to the chassis, has meant that drastic measures have been made to the traditional Singer-style looks. Where the first 911s that Singer put its stamp on were smooth, lacked fussy wings and mimicked early 911 details, the additions made to the new car look significantly more modern. The body is made entirely from carbonfibre, as before, and includes new extra wide arches – that are reminiscent of the ones found on 934 RSR race cars – covering an increased track.

The lower front bumper now features large openings for the oil cooler and an exposed carbonfibre splitter. The rear also has an exposed carbonfibre diffuser as well as a fixed ducktail spoiler. The aero devices aren’t resitricted to those you can see either, the new modifications include a completely flat floor to improve downforce without increasing drag.

Body modifications were developed using computer fluid dynamics so each element is functional and improves car’s aerodynamic efficiency. To add to the already extraordinary roster of notable people and companies involved with the DLS project, motorsport engineer Norbert Singer who worked with Porsche for 40 years, was also called in to advise on the aerodynamics.

Although they don’t look all that different, they still look a bit like the Fuchs found on old 911s, the Singer’s wheels are actually centre-lock 18-inch forged magnesium items made by BBS. Behind the wheels are a set of Brembo monoblock brake calipers and carbon ceramic disks. The Singer uses Michelin Pilot Sport Cup 2 tyres.

The entire project is a result of a commission from Scott Blattner, who wanted Singer to wanted to improve the performance of his Porsche 964. However, rather than being limited to just Blattner’s 964, Singer will modify 75 other cars with the same or similar upgrades. Rather than being built in Singer’s Californian workshop, the Williams developed upgrades will be implemented in a new studio in the UK, in Oxford. The exact price can’t be determined as each commission is different, but what you can expect is that it will be a lot of money.

This article originally appeared at

evo.co.uk